NetworkProtocols

15. ネットワーク通信プロトコル(Network communication protocols)

15.1. 概要

ネットワーク通信プロトコルは,さまざまな種類の脅威や失敗でである可能性があるネットワークの2つの部分間でデータ通信を信頼できる方法で確実に行うためのコンピュータネットワークにおける応用技術です.この科目では,脅威や失敗に遭遇した状況の事例を与え,どのようなプロトコルや符号化手順がその問題を克服するかを議論し,議論して得られた提案がどのくらい有効かを評価することで進むのが通常です.この話題は,インフラストラクチャにおけるネットワークの問題とは異なります.それは,プロトコルをどのように表すかという問題(つまり,プロトコルの設計)に焦点をあてており,プロトコルが与えられた際にすステムをどのように設定するのかということではないのです.

次は,レベル3の生徒が取り組むことができそうな概念,アルゴリズム,技術,応用,問題のリストです.この分野の重要な考え方を網羅しているわけではないことに注意してください.

15.1.1. 重要な考え方

基礎概念: 信頼性,セキュリティ,失敗,パケット損失,可読形式アドレス,サービスの品質,ネットワーク性能,サイバー攻撃,ルーティング

アルゴリズム: (この分野では,アルゴリズムよりも技術の方が適切である)

技術: パケットスイッチ,ハンドシェイク,肯定応答,認証,チェックサム,無線および有線のセキュリティ

応用: TCP/IP など多くの実際のプロトコルは,このレベルの生徒には複雑過ぎる.DNS, UDP, HTTP (GET と POST) ,IP の一部,SMTP, CDMA, SSL や IPSec や PGP などのセキュリティプロトコルは,生徒が扱えそうなそれほど複雑でないプロトコルであろう.

15.2. What is a protocol?

‘Protocol’ is a fancy word for simply saying “an agreed way to do something”. You might have heard it in a cheesy cop show -- “argh Jim, that’s against protocol!!!” -- or heard it used in a procedural sense, such as how to file a tax return or sit a driving test. We all use protocols, every day. Think of when you’re in class. The protocol for asking a question may be as follows: raise your hand, wait for a nod from the teacher then begin asking your question.

Simple tasks require simple protocols like the one above; however more complicated processes may require more complicated protocols. Pilots and aviation crew have their own language (almost) for their tasks. A subset of normal language used to convey information such as altitude, heading, people on board, status and more.

Activities on the internet vary a lot too (email, skype, video streaming, music, gaming, browsing, chatting), and so do the protocols used to achieve these. These collections of protocols form the topic of Networking Communication Protocols and this chapter will introduce you to some of them, what problems they solve, and what you can do to experience these protocols first hand. Let’s start by talking about the one you’re using if you're viewing this page on the web.

15.3. Application Level Protocols - HTTP, IRC

The URL for the home site of this book is http://csfieldguide.org. Ask a few friends what the "http" stands for - they have probably seen it thousands of times...do they know what it is? This section covers high level protocols such as HTTP and IRC, what they can do and how you can use them (hint: you’re already using HTTP right now).

15.3.1. HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

The HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the most common protocol in use on the internet. The protocol’s job is to transfer HyperText (such as HTML) from a server to your computer. It’s doing that right now. You just loaded the Field Guide from the servers where it is hosted. Hit refresh and you’ll see it in action.

HTTP functions as a simple conversation between client and server. Think of when you’re at a shop:

You: “Can I have a can of soda please?” Shop Keeper: “Sure, here’s a can of soda”

HTTP uses a request/response pattern for solving the problem of reliable communication between client and server. The “ask for” is known as a request and the reply is known as a response. Both requests and responses can also have other data or resources sent along with it.

Jargon Buster: What is a resource?

A resource is any item of data on a server. For example, a blog post, a customer, an item of stock or a news story. As a business or a website, you would create, read, update and delete these as part of your daily business. HTTP is well suited to that. For example, if you’re a news site, every day your authors would add stories, you could update them, delete them if they’re old or become out of date, all sorts. These sorts of methods are required to manage content on a server, and HTTP is the way to do this.

This is happening all the time when you're browsing the web; every web page you look at is delivered using the HyperText Transfer Protocol. Going back to the shop analogy, consider the same example, this time with more resources shown in asterisk (*) characters.

You: “Can I have a can of soda please?” *You hand the shop keeper $2* Shop Keeper: “Sure, here’s a can of soda” *Also hands you a receipt and your change*

There are nine types of requests that HTTP supports, and these are outlined below.

A GET request returns some text that describes the thing you’re asking for. Like above, you ask for a can of soda, you get a can of soda.

A HEAD request returns what you’d get if you did a GET request. It’s like this:

You: “Can I have a can of soda please?” Shop Keeper: “Sure, here’s the can of soda you’d get” *Holds up a can of soda*

What’s neat about HTTP is that it allows you to also modify the contents of the server. Say you’re now also a representative for the soda company, and you’d like to re-stock some shelves.

A POST request allows you to send information in the other direction. This request allows you to replace a resource on the server with one you supply. These use what is called a Uniform Resource Identifier or URI. A URI is a unique code or number for a resource. Confused? Let’s go back to the shop:

Sales Rep: “I’d like to replace this dented can of soda with barcode number 123-111-221 with this one, that isn’t dented” Shop Keeper: “Sure, that has now been replaced”

A PUT request adds a new resource to a server, however, if the resource already exists with that URI, it is modified with the new one.

Sales Rep: “Here, have 10 more cans of lemonade for this shelf” Shop Keeper: “Thanks, I’ve now put them on the shelf”

A DELETE request does what you’d think, it deletes a resource.

Sales Rep: “We are no longer selling ‘Lemonade with Extra Vegetables’, no one likes it! Please remove them!” Shop Keeper: “Okay, they are gone”.

Some other request types (HTTP methods) exist too, but they are less used; these are TRACE, OPTIONS, CONNECT and PATCH. You can find out more about these on your own if you're interested.

In HTTP, the first line of the response is called the status line and has a numeric status code such as 404 and a text-based reason phrase such as “Not Found”. The most common is 200 and this means successful or “OK”. HTTP status codes are primarily divided into five groups for better explanation of requests and responses between client and server and are named by purpose and a number: Informational 1XX, Successful 2XX, Redirection 3XX, Client Error 4XX and Server Error 5XX. There are many status codes for representing different cases for error or success. There’s even a nice 418: Teapot error on Google: http://www.google.com/teapot

So what’s actually happening? Well, let’s find out. If you’re in a Chrome or Safari browser, press Ctrl + Shift + I in windows or Command + Option + I on a mac to bring up the web inspector. Select the Network tab. Refresh the page. What you’re seeing now is a list of of HTTP requests your browser is making to the server to load the page you're currently viewing. Near the top you’ll see a request to NetworkCommunicationProtocols.html. Click that and you’ll see details of the Headers, Preview, Response, Cookies and Timing. Ignore those last two for now.

Let’s look at the first few lines of the headers:

Remote Address:132.181.17.3:80 Request URL: http://csfieldguide.org.nz/en/chapters/network-communication-protocols.html Request Method: GET Status Code: 200 OK

The Remote Address is the address of the server of the page is hosted on. The Request URL is the original URL that you requested. The request method should be familiar from above. It is a GET type request, saying “can I have the web page please?” and the response is the HTML. Don’t believe me? Click the Response tab. Finally, the Status Code is a code that the page can respond with.

Let’s look at the Request Headers now, click ‘view source’ to see the original request.

GET /network-communication-protocols.html HTTP/1.1 Host: www.csfieldguide.org.nz Connection: keep-alive Cache-Control: max-age=0 Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8 User-Agent: Chrome/34.0.1847.116 Accept-Encoding: gzip,deflate,sdch Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.8

As you can see, a request message consists of the following:

A request line in the form of method URI protocol/version Request Headers (Accept, User-Agent, Accept-Language etc) An empty line An optional message body.

Let’s look at the Response Headers:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sun, 11 May 2014 03:52:56 GMT

Server: Apache/2.2.15 (Red Hat)

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Content-Length: 3947

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Vary: Accept-Encoding, User-Agent

Content-Encoding: gzip

As you can see, a request message consists of the following:

- Status Line, 200 OK means everything went well.

- Response Headers (Content-Length, Content-Type etc)

- An empty line

- An optional message body.

Go ahead and try this same process on a few other pages too. For example, try these sites:

- A very busy website in terms of content, such as facebook.com

- A chapter that doesn’t exist on Google

- Your favourite website

Curiosity: Who came up with HTTP?

Tim Berners-Lee was credited for creating HTTP in 1989. You can read more about him here.

15.3.2. Internet Relay Chat (IRC)

Internet Relay Chat (IRC) is a system that lets you transfer messages in the form of text. It’s essentially a chat protocol. The system uses a client-server model. Clients are chat programs installed on a user’s computer that connect to a central server. The clients communicate the message to the central server which in turn relays that to other clients. The protocol was originally designed for group communication in a discussion forum, called channels. IRC also supports one-to-one communication via private messages. It is also capable of file and data transfer too.

The neat thing about IRC is that users can use commands to interact with the server, client or other users. For example /DIE will tell the server to shutdown (although it will only work if you are the administrator!) /ADMIN will tell you who the administrator is.

Whilst IRC may be new to you, the concept of a group conversation online or a chat room may not be. There really isn’t any difference. Groups exist in the forms of channels. A server hosts many channels, and you can choose which one to join.

Channels usually form around a particular topic, such as Python, Music, TV show fans, Gaming or Hacking. Convention dictates that channel names start with one or two # symbols, such as #python or ##TheBigBangTheory. Conventions are different to protocols in that they aren’t actually enforced by the protocol, but people choose to use it that way.

To get started with IRC, first you should get a client. A client is a program that let’s you connect Ask your teacher about which one to use. For this chapter, we’ll use the freenode web client. Check with your teacher about which channel to join, as they may have set one up for you.

Try a few things while you’re in there. Look at this list of commands and try to use some of them. What response do you get? Does this make sense?

Try a one on one conversation with a friend. If they use commands, do you see them? How about the other way around?

15.4. Transport Layer Protocols - TCP and UDP

So far we have talked about HTTP and IRC. These protocols are at a level that make sure you do not need to worry about how your data is being transported. Now we’ll cover how your data is transferred reliably and efficiently, regardless of what the data is. Below this level is an unreliable medium for transfer (such as wifi or cable, which are subject to interference errors) which causes a concern for data transportation. These protocols take different approaches to ensure data is delivered in an effective and/or efficient manner.

15.4.1. TCP

TCP (The Transmission Control Protocol) is one of the most important protocol on the internet. It breaks large messages up into packets. What is a packet? A packet is a segment of data that when combined with other packets, make up a total message (something like a HTTP request, an email, an IRC message or a file like a picture or song being downloaded). For the rest of the section, we’ll look at how these are used to load an image from a website.

So computer A looks the file and takes it, breaks it into packets. It then sends the packets over the internet and computer B reassembles them and gives them back to you as the image, which is demonstrated in this video.

By now you’re probably wondering why we bother splitting up packets… wouldn’t it be easier to send the file as a whole? Well, it solves congestion. Imagine you’re in a bus, in rush hour and you have to be home by 5. The road is jammed and there’s no way you and your friends are getting home on time. So you decide to get out of the bus and go your own separate ways. Web pages are like this too. They are too big to travel together so they are split up and sent in tiny pieces and then reassembled at the other end.

So why don’t the packets all just go from computer A to computer B just fine? Ha! That’d be nice. Unfortunately it’s not that simple. Through various means, there are some problems that can affect packets. These problems are:

- Packet loss

- Packet delay (packets arrive out of order)

- Packet corruption (the packet gets changed on the way)

So, if we didn’t try fix these, the image wouldn’t load, bits would be missing, corrupted or computer B might not even recognise what it is!

So, TCP is a protocol that solves these issues. To introduce you to TCP, play the game below, called Packet attack. In the game, you are the problems (loss, delay, corruption) and as you move through the levels, pay attention to how the computer tries to combat them. Good luck trying to stop the messages getting through correctly!

Packet Attack is a direct analogy for TCP and it is intended to be an interactive simulation of it. The Packet Creatures are TCP segments, which move between two computers. The yellow/gray zone is the unreliable channel, susceptible to unreliability. That unreliability is the user playing the game. Remember from the key problems of this topic on the transport level, we have delays, corruption and lost packets, these are the attacks; delay, corrupt, kill. Solutions come in the form of TCP mechanisms, they are slowly added level by level. Like in TCP, the game supports packet ordering, checksums (shields), Acks and Nacks (return creatures) and timeouts .

★コンテンツは準備中です★

Curiosity: Creating your own levels in packet attack

You can also create your own levels in Packet Attack. We’ve put a level builder in the projects section below so that you can experiment with different reliabilities or combination of defenses.

Adjust the trues, falses and numbers to set different abilities. Raising the numbers will effectively equate to a less reliable communication channel. Adding in more abilities (by setting shields etc to true) will make for a harder to level to beat.

Let’s talk about what you saw in that game. What did the levels do to solve the issues of packet loss, delay (reordering) and corruption? TCP has several mechanisms for dealing with packet troubles.

Curiosity: What causes delays, losses, and corruption?

Why do packets experience delays, loss and corruption? This is because as packets are sent over a network, they go through various nodes. These nodes are effectively different routers or computers. One route might experience more interference than another (causing packet loss), one might be faster or shorter than another (causing order to be lost). Corruption can happen at any time through electronic interference.

Firstly, TCP starts by doing what is known as a handshake. This basically means the two computers say to each other: “Hey, we’re going to use TCP for this image. Reconstruct it as you would”.

Next is Ordering. Since a computer can’t look at data and order it like we can (like when we do a jigsaw puzzle or play Scrabble™) they need a way to “stitch” the packets back together. As we saw in Packet Attack, if you delayed a message that didn’t have ordering, the message may look like “HELOLWOLRD”. So, TCP puts a number on each packet (called a sequence number) which signifies its order. With this, it can put them back together again. It’s a bit like when you print out a few pages from a printer and you see “Page 2 of 11” on the bottom. Now, if packets do become out of order, TCP will wait for all of the packets to arrive and then put the message together.

Another concept is checksums. This concept of storing information about the data may be familiar from the error control coding chapter. Basically, a checksum can detect errors and sometimes with coding schemes, can correct them. In the case of a correctable packet, it is corrected. If not, the packet is useless and needs to be resent. In the game, shields represent checksums. Corrupt a checksum once, and it can recover from the error using error correction. Corrupt it again and it can’t.

So how do packets get re-sent? TCP has a concept of acknowledgement and negative acknowledgement messages (ACK and NACK for short). You would have seen these in the higher levels of the game as the green (ACK) and red (NACK) creatures going back. Acks are sent to let the sender know when a packet arrives and it is usable. Nacks are sent back when a packet arrives and is damaged and needs resending. ACKs and and NACKs are useful because they provide a channel in the opposite direction for communication. If computer A receives a NACK, they can resend the message. If it receives an Ack, the computer can stop worrying about a resend.

But does a computer send it again if it doesn’t hear back? Yes. It’s called a timeout and it’s the final line of defense in TCP. If a computer doesn’t get an ACK or a NACK back, after a certain time it will just resend the packet. It’s a bit like when you’re tuning out in class, and the teacher keeps repeating your name until you answer. Maybe that’s been you… woops. Sometimes, an ACK might get lost, so the packet is resent after a timeout, but that’s OK, as TCP can recognise duplicates and ignore them.

So that’s TCP. A protocol that puts accurate data transmission before efficiency and speed in a network. It uses timeouts, checksums, acks and nacks and many packets to deliver a message reliably. However, what if we don’t need all the packets? Can we get the overall picture faster? Read on…

15.4.2. UDP

UDP (User Datagram Protocol) is a protocol for sending packets that does not guarantee delivery. UDP doesn’t guarantee against lost packets, duplicate packets or out of order packets. It just gets the bulk of the data there when it can. Checksums are used for data integrity though, so they have some protection. It’s still a protocol because it has a formal packet structure. The packets still include destination and origin as well as the size of the packet.

So do we even use such an unreliable protocol? Yes, but not for anything too important. Files, messages, emails, web pages and other text based items use TCP, but things like streaming music, video, VOIP and so on use UDP. Maybe you’ve had a call on Skype that has been poor quality. Maybe the video flickers or the sound drops for a split second. That’s packets being lost. However, you of course get the overall picture and the conversation you’re having is successful.

15.1. What's the big picture?

Think about the last time someone sent you mail via the post. They probably wrote some content on some paper, put it in an envelope, wrote an address and put it in a postbox. From there, the letter probably went into a sorting center, got sorted, and was put in a bag. The bag then went into a vehicle like a truck, plane or boat. The vehicle either travelled through water, the air, or on the road. The postal system is a complicated one, designed to let individuals communicate easily, yet being efficient enough to group many letters into one postal delivery. The same ideas apply to how messages move around the internet. Whether it be a ‘like’ on Facebook, a video stream or an email - the internet and its various protocols looks after it for you so it is delivered on time and intact to the other person.

Below we introduce some concepts, algorithms, techniques, applications and problems that relate to network protocols; it isn’t a complete list of all the ideas in the area, but should be enough to give you a good idea of what this area of computer science is about.

15.2. What is a protocol?

‘Protocol’ is a fancy word for simply saying “an agreed way to do something”. You might have heard it in a cheesy cop show -- “argh Jim, that’s against protocol!!!” -- or heard it used in a procedural sense, such as how to file a tax return or sit a driving test. We all use protocols, every day. Think of when you’re in class. The protocol for asking a question may be as follows: raise your hand, wait for a nod from the teacher then begin asking your question.

Simple tasks require simple protocols like the one above; however more complicated processes may require more complicated protocols. Pilots and aviation crew have their own language (almost) for their tasks. A subset of normal language used to convey information such as altitude, heading, people on board, status and more.

Activities on the internet vary a lot too (email, skype, video streaming, music, gaming, browsing, chatting), and so do the protocols used to achieve these. These collections of protocols form the topic of Networking Communication Protocols and this chapter will introduce you to some of them, what problems they solve, and what you can do to experience these protocols first hand. Let’s start by talking about the one you’re using if you're viewing this page on the web.

15.3. Application Level Protocols - HTTP, IRC

The URL for the home site of this book is http://csfieldguide.org. Ask a few friends what the "http" stands for - they have probably seen it thousands of times...do they know what it is? This section covers high level protocols such as HTTP and IRC, what they can do and how you can use them (hint: you’re already using HTTP right now).

15.3.1. HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

The HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the most common protocol in use on the internet. The protocol’s job is to transfer HyperText (such as HTML) from a server to your computer. It’s doing that right now. You just loaded the Field Guide from the servers where it is hosted. Hit refresh and you’ll see it in action.

HTTP functions as a simple conversation between client and server. Think of when you’re at a shop:

You: “Can I have a can of soda please?” Shop Keeper: “Sure, here’s a can of soda”

Asking for a soda

HTTP uses a request/response pattern for solving the problem of reliable communication between client and server. The “ask for” is known as a request and the reply is known as a response. Both requests and responses can also have other data or resources sent along with it.

Jargon Buster: What is a resource? ▼

A resource is any item of data on a server. For example, a blog post, a customer, an item of stock or a news story. As a business or a website, you would create, read, update and delete these as part of your daily business. HTTP is well suited to that. For example, if you’re a news site, every day your authors would add stories, you could update them, delete them if they’re old or become out of date, all sorts. These sorts of methods are required to manage content on a server, and HTTP is the way to do this.

This is happening all the time when you're browsing the web; every web page you look at is delivered using the HyperText Transfer Protocol. Going back to the shop analogy, consider the same example, this time with more resources shown in asterisk (*) characters.

You: “Can I have a can of soda please?” *You hand the shop keeper $2* Shop Keeper: “Sure, here’s a can of soda” *Also hands you a receipt and your change*

Paying for a soda with cash

There are nine types of requests that HTTP supports, and these are outlined below.

A GET request returns some text that describes the thing you’re asking for. Like above, you ask for a can of soda, you get a can of soda.

A HEAD request returns what you’d get if you did a GET request. It’s like this:

You: “Can I have a can of soda please?” Shop Keeper: “Sure, here’s the can of soda you’d get” *Holds up a can of soda*

What’s neat about HTTP is that it allows you to also modify the contents of the server. Say you’re now also a representative for the soda company, and you’d like to re-stock some shelves.

A POST request allows you to send information in the other direction. This request allows you to replace a resource on the server with one you supply. These use what is called a Uniform Resource Identifier or URI. A URI is a unique code or number for a resource. Confused? Let’s go back to the shop:

Sales Rep: “I’d like to replace this dented can of soda with barcode number 123-111-221 with this one, that isn’t dented” Shop Keeper: “Sure, that has now been replaced”

A PUT request adds a new resource to a server, however, if the resource already exists with that URI, it is modified with the new one.

Sales Rep: “Here, have 10 more cans of lemonade for this shelf” Shop Keeper: “Thanks, I’ve now put them on the shelf”

A DELETE request does what you’d think, it deletes a resource.

Sales Rep: “We are no longer selling ‘Lemonade with Extra Vegetables’, no one likes it! Please remove them!” Shop Keeper: “Okay, they are gone”.

Some other request types (HTTP methods) exist too, but they are less used; these are TRACE, OPTIONS, CONNECT and PATCH. You can find out more about these on your own if you're interested.

In HTTP, the first line of the response is called the status line and has a numeric status code such as 404 and a text-based reason phrase such as “Not Found”. The most common is 200 and this means successful or “OK”. HTTP status codes are primarily divided into five groups for better explanation of requests and responses between client and server and are named by purpose and a number: Informational 1XX, Successful 2XX, Redirection 3XX, Client Error 4XX and Server Error 5XX. There are many status codes for representing different cases for error or success. There’s even a nice 418: Teapot error on Google: http://www.google.com/teapot

So what’s actually happening? Well, let’s find out. If you’re in a Chrome or Safari browser, press Ctrl + Shift + I in windows or Command + Option + I on a mac to bring up the web inspector. Select the Network tab. Refresh the page. What you’re seeing now is a list of of HTTP requests your browser is making to the server to load the page you're currently viewing. Near the top you’ll see a request to NetworkCommunicationProtocols.html. Click that and you’ll see details of the Headers, Preview, Response, Cookies and Timing. Ignore those last two for now.

Let’s look at the first few lines of the headers:

Remote Address:132.181.17.3:80

Request URL: http://csfieldguide.org.nz/en/chapters/network-communication-protocols.html

Request Method: GET

Status Code: 200 OK

The Remote Address is the address of the server of the page is hosted on. The Request URL is the original URL that you requested. The request method should be familiar from above. It is a GET type request, saying “can I have the web page please?” and the response is the HTML. Don’t believe me? Click the Response tab. Finally, the Status Code is a code that the page can respond with.

Let’s look at the Request Headers now, click ‘view source’ to see the original request.

GET /network-communication-protocols.html HTTP/1.1

Host: www.csfieldguide.org.nz

Connection: keep-alive

Cache-Control: max-age=0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

User-Agent: Chrome/34.0.1847.116

Accept-Encoding: gzip,deflate,sdch

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.8

As you can see, a request message consists of the following:

A request line in the form of method URI protocol/version Request Headers (Accept, User-Agent, Accept-Language etc) An empty line An optional message body.

Let’s look at the Response Headers:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sun, 11 May 2014 03:52:56 GMT

Server: Apache/2.2.15 (Red Hat)

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Content-Length: 3947

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Vary: Accept-Encoding, User-Agent

Content-Encoding: gzip

As you can see, a request message consists of the following:

Status Line, 200 OK means everything went well. Response Headers (Content-Length, Content-Type etc) An empty line An optional message body.

Go ahead and try this same process on a few other pages too. For example, try these sites:

A very busy website in terms of content, such as facebook.com A chapter that doesn’t exist on Google Your favourite website

Curiosity: Who came up with HTTP? ▼

Tim Berners-Lee was credited for creating HTTP in 1989. You can read more about him here.

15.3.2. Internet Relay Chat (IRC)

Internet Relay Chat (IRC) is a system that lets you transfer messages in the form of text. It’s essentially a chat protocol. The system uses a client-server model. Clients are chat programs installed on a user’s computer that connect to a central server. The clients communicate the message to the central server which in turn relays that to other clients. The protocol was originally designed for group communication in a discussion forum, called channels. IRC also supports one-to-one communication via private messages. It is also capable of file and data transfer too.

The neat thing about IRC is that users can use commands to interact with the server, client or other users. For example /DIE will tell the server to shutdown (although it will only work if you are the administrator!) /ADMIN will tell you who the administrator is.

Whilst IRC may be new to you, the concept of a group conversation online or a chat room may not be. There really isn’t any difference. Groups exist in the forms of channels. A server hosts many channels, and you can choose which one to join.

Channels usually form around a particular topic, such as Python, Music, TV show fans, Gaming or Hacking. Convention dictates that channel names start with one or two # symbols, such as #python or ##TheBigBangTheory. Conventions are different to protocols in that they aren’t actually enforced by the protocol, but people choose to use it that way.

To get started with IRC, first you should get a client. A client is a program that let’s you connect Ask your teacher about which one to use. For this chapter, we’ll use the freenode web client. Check with your teacher about which channel to join, as they may have set one up for you.

Try a few things while you’re in there. Look at this list of commands and try to use some of them. What response do you get? Does this make sense?

Try a one on one conversation with a friend. If they use commands, do you see them? How about the other way around?

15.4. Transport Layer Protocols - TCP and UDP

So far we have talked about HTTP and IRC. These protocols are at a level that make sure you do not need to worry about how your data is being transported. Now we’ll cover how your data is transferred reliably and efficiently, regardless of what the data is. Below this level is an unreliable medium for transfer (such as wifi or cable, which are subject to interference errors) which causes a concern for data transportation. These protocols take different approaches to ensure data is delivered in an effective and/or efficient manner.

15.4.1. TCP

TCP (The Transmission Control Protocol) is one of the most important protocol on the internet. It breaks large messages up into packets. What is a packet? A packet is a segment of data that when combined with other packets, make up a total message (something like a HTTP request, an email, an IRC message or a file like a picture or song being downloaded). For the rest of the section, we’ll look at how these are used to load an image from a website.

So computer A looks the file and takes it, breaks it into packets. It then sends the packets over the internet and computer B reassembles them and gives them back to you as the image, which is demonstrated in this video.

By now you’re probably wondering why we bother splitting up packets… wouldn’t it be easier to send the file as a whole? Well, it solves congestion. Imagine you’re in a bus, in rush hour and you have to be home by 5. The road is jammed and there’s no way you and your friends are getting home on time. So you decide to get out of the bus and go your own separate ways. Web pages are like this too. They are too big to travel together so they are split up and sent in tiny pieces and then reassembled at the other end.

So why don’t the packets all just go from computer A to computer B just fine? Ha! That’d be nice. Unfortunately it’s not that simple. Through various means, there are some problems that can affect packets. These problems are:

Packet loss Packet delay (packets arrive out of order) Packet corruption (the packet gets changed on the way)

So, if we didn’t try fix these, the image wouldn’t load, bits would be missing, corrupted or computer B might not even recognise what it is!

Corrupted Image

So, TCP is a protocol that solves these issues. To introduce you to TCP, play the game below, called Packet attack. In the game, you are the problems (loss, delay, corruption) and as you move through the levels, pay attention to how the computer tries to combat them. Good luck trying to stop the messages getting through correctly!

Packet Attack is a direct analogy for TCP and it is intended to be an interactive simulation of it. The Packet Creatures are TCP segments, which move between two computers. The yellow/gray zone is the unreliable channel, susceptible to unreliability. That unreliability is the user playing the game. Remember from the key problems of this topic on the transport level, we have delays, corruption and lost packets, these are the attacks; delay, corrupt, kill. Solutions come in the form of TCP mechanisms, they are slowly added level by level. Like in TCP, the game supports packet ordering, checksums (shields), Acks and Nacks (return creatures) and timeouts .

Click to load Packet Attack interactive

Curiosity: Creating your own levels in packet attack ▼

You can also create your own levels in Packet Attack. We’ve put a level builder in the projects section below so that you can experiment with different reliabilities or combination of defenses.

Adjust the trues, falses and numbers to set different abilities. Raising the numbers will effectively equate to a less reliable communication channel. Adding in more abilities (by setting shields etc to true) will make for a harder to level to beat.

Let’s talk about what you saw in that game. What did the levels do to solve the issues of packet loss, delay (reordering) and corruption? TCP has several mechanisms for dealing with packet troubles.

Curiosity: What causes delays, losses, and corruption? ▼

Why do packets experience delays, loss and corruption? This is because as packets are sent over a network, they go through various nodes. These nodes are effectively different routers or computers. One route might experience more interference than another (causing packet loss), one might be faster or shorter than another (causing order to be lost). Corruption can happen at any time through electronic interference.

Firstly, TCP starts by doing what is known as a handshake. This basically means the two computers say to each other: “Hey, we’re going to use TCP for this image. Reconstruct it as you would”.

Next is Ordering. Since a computer can’t look at data and order it like we can (like when we do a jigsaw puzzle or play Scrabble™) they need a way to “stitch” the packets back together. As we saw in Packet Attack, if you delayed a message that didn’t have ordering, the message may look like “HELOLWOLRD”. So, TCP puts a number on each packet (called a sequence number) which signifies its order. With this, it can put them back together again. It’s a bit like when you print out a few pages from a printer and you see “Page 2 of 11” on the bottom. Now, if packets do become out of order, TCP will wait for all of the packets to arrive and then put the message together.

Another concept is checksums. This concept of storing information about the data may be familiar from the error control coding chapter. Basically, a checksum can detect errors and sometimes with coding schemes, can correct them. In the case of a correctable packet, it is corrected. If not, the packet is useless and needs to be resent. In the game, shields represent checksums. Corrupt a checksum once, and it can recover from the error using error correction. Corrupt it again and it can’t.

So how do packets get re-sent? TCP has a concept of acknowledgement and negative acknowledgement messages (ACK and NACK for short). You would have seen these in the higher levels of the game as the green (ACK) and red (NACK) creatures going back. Acks are sent to let the sender know when a packet arrives and it is usable. Nacks are sent back when a packet arrives and is damaged and needs resending. ACKs and and NACKs are useful because they provide a channel in the opposite direction for communication. If computer A receives a NACK, they can resend the message. If it receives an Ack, the computer can stop worrying about a resend.

But does a computer send it again if it doesn’t hear back? Yes. It’s called a timeout and it’s the final line of defense in TCP. If a computer doesn’t get an ACK or a NACK back, after a certain time it will just resend the packet. It’s a bit like when you’re tuning out in class, and the teacher keeps repeating your name until you answer. Maybe that’s been you… woops. Sometimes, an ACK might get lost, so the packet is resent after a timeout, but that’s OK, as TCP can recognise duplicates and ignore them.

So that’s TCP. A protocol that puts accurate data transmission before efficiency and speed in a network. It uses timeouts, checksums, acks and nacks and many packets to deliver a message reliably. However, what if we don’t need all the packets? Can we get the overall picture faster? Read on…

15.4.2. UDP

UDP (User Datagram Protocol) is a protocol for sending packets that does not guarantee delivery. UDP doesn’t guarantee against lost packets, duplicate packets or out of order packets. It just gets the bulk of the data there when it can. Checksums are used for data integrity though, so they have some protection. It’s still a protocol because it has a formal packet structure. The packets still include destination and origin as well as the size of the packet.

So do we even use such an unreliable protocol? Yes, but not for anything too important. Files, messages, emails, web pages and other text based items use TCP, but things like streaming music, video, VOIP and so on use UDP. Maybe you’ve had a call on Skype that has been poor quality. Maybe the video flickers or the sound drops for a split second. That’s packets being lost. However, you of course get the overall picture and the conversation you’re having is successful.

15.5. The Whole Story

Let’s say I want to write an online music player. Okay, so I write the code for someone to press play on a website and the song plays. Do I now need to code up the protocol that streams the music? Fine, I write some UDP code. Now, do I need to go install the cables in your house? Sure, I jump in my van and spend a few weeks running cable to your house and make sure the packets can get over too.

No. This sounds absurd. As a web developer, I don’t want to worry about anything other than making my music player easy to use and fast. I don’t want to worry about UDP and I don’t want to worry about ethernet or cables. It’s already done, I can assume it’s take care of. And it is.

Internet protocols exist in layers. We have four such layers in the computer science internet model. The top two levels are discussed above in detail, the bottom two we won’t focus on.The first layer is the Application Layer, followed by the Transport, Internet and Link layers.

At each layer, data is made up of the previous layers’ whole unit of data, and then headers are added and passed down. At the bottom layer, the Link layer, a footer is added also. Below is an example of what a UDP packet looks like when it’s packaged up for transport.

Jargon Buster: Headers and footers

Footers and Headers are basically packet meta-data. Information about the information. Like a letterhead or a footnote, they’re not part of the content, but they are on the page. Headers and Footers exist on packets to store data. Headers come before the data and footers afterwards.

You can think of these protocols as a game of pass the parcel. When a message is sent in HTTP, it is wrapped in a TCP header, which is then wrapped in an IPv6 header, which is then wrapped in a Ethernet header and footer and sent over ethernet. At the other end, it’s unwrapped again from an ethernet frame, back to a IP packet, a TCP datagram, to a HTTP request.

Curiosity: What is a Packet?

The name packet is a generic term for a unit of data. In the application layer units of data are called data or requests, in the transport layer, datagram or segments, in the Network/IP layer, packet and in the physical layer, a frame. Each level has its own name for a unit of data (segment, packet, frame, request etc), however the more generic “packet” is often used instead, regardless of layer.

This system is neat because each layer can assume that the layer above and below have guaranteed something about the information, and each layer (and protocol in use at that layer) has a stand-alone role. So if you’re making a website you just have to program website code, and not worry about code to make the site work over wifi as well as ethernet. A similar system is in the postal system… You don’t put the courier’s truck number on the front of the envelope! That’s take care of by the post company, which then uses a system to sort the mail and assign it to drivers, and then drivers to trucks, and then drivers to routes… none of which you need to worry about when you send or receive a letter or use a courier.

Curiosity: The OSI model vs the TCP/IP model

The OSI internet model is different from the TCP/IP model of the internet that Computer Scientists use to approach protocol design. OSI is considered and probably mentioned in the networking standards but the guide will use the computer science approach because it is simpler, however the main idea of layers of abstraction is more important to get across. You can read more about the differences here.

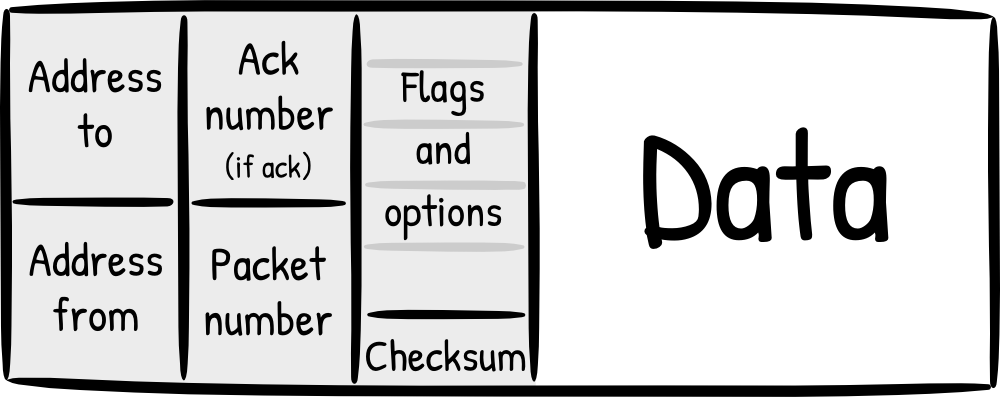

So what does a TCP segment look like?

As you can see, a packet is divided into four main parts, addresses (source, destination), numbers (sequence number, ANCK number if it’s an acknowledgement), flags (urgent, checksum) in the header, then the actual data. At each level, a segment becomes the data for the next data unit, and that again gets its own header.

TCP and UDP packets have a number with how big they are. This number means that the packet can actually be as big as you like. Can you think of any advantages of having small packets? How about big ones? Think about the ratio of data to information (such as those in the header and footer).

Curiosity: What does a packet trace look like?

Here’s an example of a packet trace on our network…(using tcpdump on the mac)

00:55:18.540237 b8:e8:56:02:f8:3e > c4:a8:1d:17:a0:d3, ethertype IPv4 (0x0800), length 100: (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 41564, offset 0, flags [none], proto UDP (17), length 86) 192.168.1.7.51413 > 37.48.71.67.63412: [udp sum ok] UDP, length 58 0x0000: 4500 0056 a25c 0000 4011 aa18 c0a8 0107 0x0010: 2530 4743 c8d5 f7b4 0042 1c72 6431 3a61 0x0020: 6432 3a69 6432 303a b785 2dc9 2e78 e7fb 0x0030: 68c3 81ab e28b fde3 cfef ae47 6531 3a71 0x0040: 343a 7069 6e67 313a 7434 3a70 6e00 0031 0x0050: 3a79 313a 7165

15.6. Further reading

- The two generals problem is a famous problem in protocols to talk about what happens when you can’t be sure about communication success

- What happens if you were to send packets tied to birds? IP over Avian Cariers

- Protocols are found in the strangest of places…. Engine Order Telegraph

- Coursera course on Internet History, Technology, and Security

15.1. What's the big picture?

Think about the last time someone sent you mail via the post. They probably wrote some content on some paper, put it in an envelope, wrote an address and put it in a postbox. From there, the letter probably went into a sorting center, got sorted, and was put in a bag. The bag then went into a vehicle like a truck, plane or boat. The vehicle either travelled through water, the air, or on the road. The postal system is a complicated one, designed to let individuals communicate easily, yet being efficient enough to group many letters into one postal delivery. The same ideas apply to how messages move around the internet. Whether it be a ‘like’ on Facebook, a video stream or an email - the internet and its various protocols looks after it for you so it is delivered on time and intact to the other person.

Below we introduce some concepts, algorithms, techniques, applications and problems that relate to network protocols; it isn’t a complete list of all the ideas in the area, but should be enough to give you a good idea of what this area of computer science is about.

15.2. What is a protocol?

‘Protocol’ is a fancy word for simply saying “an agreed way to do something”. You might have heard it in a cheesy cop show -- “argh Jim, that’s against protocol!!!” -- or heard it used in a procedural sense, such as how to file a tax return or sit a driving test. We all use protocols, every day. Think of when you’re in class. The protocol for asking a question may be as follows: raise your hand, wait for a nod from the teacher then begin asking your question.

Simple tasks require simple protocols like the one above; however more complicated processes may require more complicated protocols. Pilots and aviation crew have their own language (almost) for their tasks. A subset of normal language used to convey information such as altitude, heading, people on board, status and more.

Activities on the internet vary a lot too (email, skype, video streaming, music, gaming, browsing, chatting), and so do the protocols used to achieve these. These collections of protocols form the topic of Networking Communication Protocols and this chapter will introduce you to some of them, what problems they solve, and what you can do to experience these protocols first hand. Let’s start by talking about the one you’re using if you're viewing this page on the web.

15.3. Application Level Protocols - HTTP, IRC

The URL for the home site of this book is http://csfieldguide.org. Ask a few friends what the "http" stands for - they have probably seen it thousands of times...do they know what it is? This section covers high level protocols such as HTTP and IRC, what they can do and how you can use them (hint: you’re already using HTTP right now).

15.3.1. HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

The HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the most common protocol in use on the internet. The protocol’s job is to transfer HyperText (such as HTML) from a server to your computer. It’s doing that right now. You just loaded the Field Guide from the servers where it is hosted. Hit refresh and you’ll see it in action.

HTTP functions as a simple conversation between client and server. Think of when you’re at a shop:

You: “Can I have a can of soda please?” Shop Keeper: “Sure, here’s a can of soda”

Asking for a soda

HTTP uses a request/response pattern for solving the problem of reliable communication between client and server. The “ask for” is known as a request and the reply is known as a response. Both requests and responses can also have other data or resources sent along with it.

Jargon Buster: What is a resource? ▼

A resource is any item of data on a server. For example, a blog post, a customer, an item of stock or a news story. As a business or a website, you would create, read, update and delete these as part of your daily business. HTTP is well suited to that. For example, if you’re a news site, every day your authors would add stories, you could update them, delete them if they’re old or become out of date, all sorts. These sorts of methods are required to manage content on a server, and HTTP is the way to do this.

This is happening all the time when you're browsing the web; every web page you look at is delivered using the HyperText Transfer Protocol. Going back to the shop analogy, consider the same example, this time with more resources shown in asterisk (*) characters.

You: “Can I have a can of soda please?” *You hand the shop keeper $2* Shop Keeper: “Sure, here’s a can of soda” *Also hands you a receipt and your change*

Paying for a soda with cash

There are nine types of requests that HTTP supports, and these are outlined below.

A GET request returns some text that describes the thing you’re asking for. Like above, you ask for a can of soda, you get a can of soda.

A HEAD request returns what you’d get if you did a GET request. It’s like this:

You: “Can I have a can of soda please?” Shop Keeper: “Sure, here’s the can of soda you’d get” *Holds up a can of soda*

What’s neat about HTTP is that it allows you to also modify the contents of the server. Say you’re now also a representative for the soda company, and you’d like to re-stock some shelves.

A POST request allows you to send information in the other direction. This request allows you to replace a resource on the server with one you supply. These use what is called a Uniform Resource Identifier or URI. A URI is a unique code or number for a resource. Confused? Let’s go back to the shop:

Sales Rep: “I’d like to replace this dented can of soda with barcode number 123-111-221 with this one, that isn’t dented” Shop Keeper: “Sure, that has now been replaced”

A PUT request adds a new resource to a server, however, if the resource already exists with that URI, it is modified with the new one.

Sales Rep: “Here, have 10 more cans of lemonade for this shelf” Shop Keeper: “Thanks, I’ve now put them on the shelf”

A DELETE request does what you’d think, it deletes a resource.

Sales Rep: “We are no longer selling ‘Lemonade with Extra Vegetables’, no one likes it! Please remove them!” Shop Keeper: “Okay, they are gone”.

Some other request types (HTTP methods) exist too, but they are less used; these are TRACE, OPTIONS, CONNECT and PATCH. You can find out more about these on your own if you're interested.

In HTTP, the first line of the response is called the status line and has a numeric status code such as 404 and a text-based reason phrase such as “Not Found”. The most common is 200 and this means successful or “OK”. HTTP status codes are primarily divided into five groups for better explanation of requests and responses between client and server and are named by purpose and a number: Informational 1XX, Successful 2XX, Redirection 3XX, Client Error 4XX and Server Error 5XX. There are many status codes for representing different cases for error or success. There’s even a nice 418: Teapot error on Google: http://www.google.com/teapot

So what’s actually happening? Well, let’s find out. If you’re in a Chrome or Safari browser, press Ctrl + Shift + I in windows or Command + Option + I on a mac to bring up the web inspector. Select the Network tab. Refresh the page. What you’re seeing now is a list of of HTTP requests your browser is making to the server to load the page you're currently viewing. Near the top you’ll see a request to NetworkCommunicationProtocols.html. Click that and you’ll see details of the Headers, Preview, Response, Cookies and Timing. Ignore those last two for now.

Let’s look at the first few lines of the headers:

Remote Address:132.181.17.3:80

Request URL: http://csfieldguide.org.nz/en/chapters/network-communication-protocols.html

Request Method: GET

Status Code: 200 OK

The Remote Address is the address of the server of the page is hosted on. The Request URL is the original URL that you requested. The request method should be familiar from above. It is a GET type request, saying “can I have the web page please?” and the response is the HTML. Don’t believe me? Click the Response tab. Finally, the Status Code is a code that the page can respond with.

Let’s look at the Request Headers now, click ‘view source’ to see the original request.

GET /network-communication-protocols.html HTTP/1.1

Host: www.csfieldguide.org.nz

Connection: keep-alive

Cache-Control: max-age=0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

User-Agent: Chrome/34.0.1847.116

Accept-Encoding: gzip,deflate,sdch

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.8

As you can see, a request message consists of the following:

A request line in the form of method URI protocol/version Request Headers (Accept, User-Agent, Accept-Language etc) An empty line An optional message body.

Let’s look at the Response Headers:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sun, 11 May 2014 03:52:56 GMT

Server: Apache/2.2.15 (Red Hat)

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Content-Length: 3947

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Vary: Accept-Encoding, User-Agent

Content-Encoding: gzip

As you can see, a request message consists of the following:

Status Line, 200 OK means everything went well. Response Headers (Content-Length, Content-Type etc) An empty line An optional message body.

Go ahead and try this same process on a few other pages too. For example, try these sites:

A very busy website in terms of content, such as facebook.com A chapter that doesn’t exist on Google Your favourite website

Curiosity: Who came up with HTTP? ▼

Tim Berners-Lee was credited for creating HTTP in 1989. You can read more about him here.

15.3.2. Internet Relay Chat (IRC)

Internet Relay Chat (IRC) is a system that lets you transfer messages in the form of text. It’s essentially a chat protocol. The system uses a client-server model. Clients are chat programs installed on a user’s computer that connect to a central server. The clients communicate the message to the central server which in turn relays that to other clients. The protocol was originally designed for group communication in a discussion forum, called channels. IRC also supports one-to-one communication via private messages. It is also capable of file and data transfer too.

The neat thing about IRC is that users can use commands to interact with the server, client or other users. For example /DIE will tell the server to shutdown (although it will only work if you are the administrator!) /ADMIN will tell you who the administrator is.

Whilst IRC may be new to you, the concept of a group conversation online or a chat room may not be. There really isn’t any difference. Groups exist in the forms of channels. A server hosts many channels, and you can choose which one to join.

Channels usually form around a particular topic, such as Python, Music, TV show fans, Gaming or Hacking. Convention dictates that channel names start with one or two # symbols, such as #python or ##TheBigBangTheory. Conventions are different to protocols in that they aren’t actually enforced by the protocol, but people choose to use it that way.

To get started with IRC, first you should get a client. A client is a program that let’s you connect Ask your teacher about which one to use. For this chapter, we’ll use the freenode web client. Check with your teacher about which channel to join, as they may have set one up for you.

Try a few things while you’re in there. Look at this list of commands and try to use some of them. What response do you get? Does this make sense?

Try a one on one conversation with a friend. If they use commands, do you see them? How about the other way around?

15.4. Transport Layer Protocols - TCP and UDP

So far we have talked about HTTP and IRC. These protocols are at a level that make sure you do not need to worry about how your data is being transported. Now we’ll cover how your data is transferred reliably and efficiently, regardless of what the data is. Below this level is an unreliable medium for transfer (such as wifi or cable, which are subject to interference errors) which causes a concern for data transportation. These protocols take different approaches to ensure data is delivered in an effective and/or efficient manner.

15.4.1. TCP

TCP (The Transmission Control Protocol) is one of the most important protocol on the internet. It breaks large messages up into packets. What is a packet? A packet is a segment of data that when combined with other packets, make up a total message (something like a HTTP request, an email, an IRC message or a file like a picture or song being downloaded). For the rest of the section, we’ll look at how these are used to load an image from a website.

So computer A looks the file and takes it, breaks it into packets. It then sends the packets over the internet and computer B reassembles them and gives them back to you as the image, which is demonstrated in this video.

By now you’re probably wondering why we bother splitting up packets… wouldn’t it be easier to send the file as a whole? Well, it solves congestion. Imagine you’re in a bus, in rush hour and you have to be home by 5. The road is jammed and there’s no way you and your friends are getting home on time. So you decide to get out of the bus and go your own separate ways. Web pages are like this too. They are too big to travel together so they are split up and sent in tiny pieces and then reassembled at the other end.

So why don’t the packets all just go from computer A to computer B just fine? Ha! That’d be nice. Unfortunately it’s not that simple. Through various means, there are some problems that can affect packets. These problems are:

Packet loss Packet delay (packets arrive out of order) Packet corruption (the packet gets changed on the way)

So, if we didn’t try fix these, the image wouldn’t load, bits would be missing, corrupted or computer B might not even recognise what it is!

Corrupted Image

So, TCP is a protocol that solves these issues. To introduce you to TCP, play the game below, called Packet attack. In the game, you are the problems (loss, delay, corruption) and as you move through the levels, pay attention to how the computer tries to combat them. Good luck trying to stop the messages getting through correctly!

Packet Attack is a direct analogy for TCP and it is intended to be an interactive simulation of it. The Packet Creatures are TCP segments, which move between two computers. The yellow/gray zone is the unreliable channel, susceptible to unreliability. That unreliability is the user playing the game. Remember from the key problems of this topic on the transport level, we have delays, corruption and lost packets, these are the attacks; delay, corrupt, kill. Solutions come in the form of TCP mechanisms, they are slowly added level by level. Like in TCP, the game supports packet ordering, checksums (shields), Acks and Nacks (return creatures) and timeouts .

Click to load Packet Attack interactive

Curiosity: Creating your own levels in packet attack ▼

You can also create your own levels in Packet Attack. We’ve put a level builder in the projects section below so that you can experiment with different reliabilities or combination of defenses.

Adjust the trues, falses and numbers to set different abilities. Raising the numbers will effectively equate to a less reliable communication channel. Adding in more abilities (by setting shields etc to true) will make for a harder to level to beat.

Let’s talk about what you saw in that game. What did the levels do to solve the issues of packet loss, delay (reordering) and corruption? TCP has several mechanisms for dealing with packet troubles.

Curiosity: What causes delays, losses, and corruption? ▼

Why do packets experience delays, loss and corruption? This is because as packets are sent over a network, they go through various nodes. These nodes are effectively different routers or computers. One route might experience more interference than another (causing packet loss), one might be faster or shorter than another (causing order to be lost). Corruption can happen at any time through electronic interference.

Firstly, TCP starts by doing what is known as a handshake. This basically means the two computers say to each other: “Hey, we’re going to use TCP for this image. Reconstruct it as you would”.

Next is Ordering. Since a computer can’t look at data and order it like we can (like when we do a jigsaw puzzle or play Scrabble™) they need a way to “stitch” the packets back together. As we saw in Packet Attack, if you delayed a message that didn’t have ordering, the message may look like “HELOLWOLRD”. So, TCP puts a number on each packet (called a sequence number) which signifies its order. With this, it can put them back together again. It’s a bit like when you print out a few pages from a printer and you see “Page 2 of 11” on the bottom. Now, if packets do become out of order, TCP will wait for all of the packets to arrive and then put the message together.

Another concept is checksums. This concept of storing information about the data may be familiar from the error control coding chapter. Basically, a checksum can detect errors and sometimes with coding schemes, can correct them. In the case of a correctable packet, it is corrected. If not, the packet is useless and needs to be resent. In the game, shields represent checksums. Corrupt a checksum once, and it can recover from the error using error correction. Corrupt it again and it can’t.

So how do packets get re-sent? TCP has a concept of acknowledgement and negative acknowledgement messages (ACK and NACK for short). You would have seen these in the higher levels of the game as the green (ACK) and red (NACK) creatures going back. Acks are sent to let the sender know when a packet arrives and it is usable. Nacks are sent back when a packet arrives and is damaged and needs resending. ACKs and and NACKs are useful because they provide a channel in the opposite direction for communication. If computer A receives a NACK, they can resend the message. If it receives an Ack, the computer can stop worrying about a resend.

But does a computer send it again if it doesn’t hear back? Yes. It’s called a timeout and it’s the final line of defense in TCP. If a computer doesn’t get an ACK or a NACK back, after a certain time it will just resend the packet. It’s a bit like when you’re tuning out in class, and the teacher keeps repeating your name until you answer. Maybe that’s been you… woops. Sometimes, an ACK might get lost, so the packet is resent after a timeout, but that’s OK, as TCP can recognise duplicates and ignore them.

So that’s TCP. A protocol that puts accurate data transmission before efficiency and speed in a network. It uses timeouts, checksums, acks and nacks and many packets to deliver a message reliably. However, what if we don’t need all the packets? Can we get the overall picture faster? Read on…

15.4.2. UDP

UDP (User Datagram Protocol) is a protocol for sending packets that does not guarantee delivery. UDP doesn’t guarantee against lost packets, duplicate packets or out of order packets. It just gets the bulk of the data there when it can. Checksums are used for data integrity though, so they have some protection. It’s still a protocol because it has a formal packet structure. The packets still include destination and origin as well as the size of the packet.

So do we even use such an unreliable protocol? Yes, but not for anything too important. Files, messages, emails, web pages and other text based items use TCP, but things like streaming music, video, VOIP and so on use UDP. Maybe you’ve had a call on Skype that has been poor quality. Maybe the video flickers or the sound drops for a split second. That’s packets being lost. However, you of course get the overall picture and the conversation you’re having is successful.

15.5. The Whole Story

Let’s say I want to write an online music player. Okay, so I write the code for someone to press play on a website and the song plays. Do I now need to code up the protocol that streams the music? Fine, I write some UDP code. Now, do I need to go install the cables in your house? Sure, I jump in my van and spend a few weeks running cable to your house and make sure the packets can get over too.

No. This sounds absurd. As a web developer, I don’t want to worry about anything other than making my music player easy to use and fast. I don’t want to worry about UDP and I don’t want to worry about ethernet or cables. It’s already done, I can assume it’s take care of. And it is.

Internet protocols exist in layers. We have four such layers in the computer science internet model. The top two levels are discussed above in detail, the bottom two we won’t focus on.The first layer is the Application Layer, followed by the Transport, Internet and Link layers.

At each layer, data is made up of the previous layers’ whole unit of data, and then headers are added and passed down. At the bottom layer, the Link layer, a footer is added also. Below is an example of what a UDP packet looks like when it’s packaged up for transport.

Jargon Buster: Headers and footers ▼

Footers and Headers are basically packet meta-data. Information about the information. Like a letterhead or a footnote, they’re not part of the content, but they are on the page. Headers and Footers exist on packets to store data. Headers come before the data and footers afterwards.

You can think of these protocols as a game of pass the parcel. When a message is sent in HTTP, it is wrapped in a TCP header, which is then wrapped in an IPv6 header, which is then wrapped in a Ethernet header and footer and sent over ethernet. At the other end, it’s unwrapped again from an ethernet frame, back to a IP packet, a TCP datagram, to a HTTP request.

Curiosity: What is a Packet? ▼

The name packet is a generic term for a unit of data. In the application layer units of data are called data or requests, in the transport layer, datagram or segments, in the Network/IP layer, packet and in the physical layer, a frame. Each level has its own name for a unit of data (segment, packet, frame, request etc), however the more generic “packet” is often used instead, regardless of layer.

This system is neat because each layer can assume that the layer above and below have guaranteed something about the information, and each layer (and protocol in use at that layer) has a stand-alone role. So if you’re making a website you just have to program website code, and not worry about code to make the site work over wifi as well as ethernet. A similar system is in the postal system… You don’t put the courier’s truck number on the front of the envelope! That’s take care of by the post company, which then uses a system to sort the mail and assign it to drivers, and then drivers to trucks, and then drivers to routes… none of which you need to worry about when you send or receive a letter or use a courier.

Curiosity: The OSI model vs the TCP/IP model ▼

The OSI internet model is different from the TCP/IP model of the internet that Computer Scientists use to approach protocol design. OSI is considered and probably mentioned in the networking standards but the guide will use the computer science approach because it is simpler, however the main idea of layers of abstraction is more important to get across. You can read more about the differences here.

So what does a TCP segment look like?

Showing the structure of a TCP packet

As you can see, a packet is divided into four main parts, addresses (source, destination), numbers (sequence number, ANCK number if it’s an acknowledgement), flags (urgent, checksum) in the header, then the actual data. At each level, a segment becomes the data for the next data unit, and that again gets its own header.

TCP and UDP packets have a number with how big they are. This number means that the packet can actually be as big as you like. Can you think of any advantages of having small packets? How about big ones? Think about the ratio of data to information (such as those in the header and footer).

Curiosity: What does a packet trace look like?

Here’s an example of a packet trace on our network…(using tcpdump on the mac)

00:55:18.540237 b8:e8:56:02:f8:3e > c4:a8:1d:17:a0:d3, ethertype IPv4 (0x0800), length 100: (tos 0x0, ttl 64, id 41564, offset 0, flags [none], proto UDP (17), length 86)

192.168.1.7.51413 > 37.48.71.67.63412: [udp sum ok] UDP, length 58

0x0000: 4500 0056 a25c 0000 4011 aa18 c0a8 0107

0x0010: 2530 4743 c8d5 f7b4 0042 1c72 6431 3a61

0x0020: 6432 3a69 6432 303a b785 2dc9 2e78 e7fb

0x0030: 68c3 81ab e28b fde3 cfef ae47 6531 3a71

0x0040: 343a 7069 6e67 313a 7434 3a70 6e00 0031

0x0050: 3a79 313a 7165

15.6. Further reading

The two generals problem is a famous problem in protocols to talk about what happens when you can’t be sure about communication success What happens if you were to send packets tied to birds? IP over Avian Cariers Protocols are found in the strangest of places…. Engine Order Telegraph Coursera course on Internet History, Technology, and Security

15.6.1. Videos

There and back again: a packet's tale

★コンテンツの追加(Youtube)

How does the internet work?

★コンテンツの追加(Youtube)

How the internet works in 5 minutes

★コンテンツの追加(Youtube)

15.6.2. Extra Activities

CS Unplugged Routing - Why do packets get delayed? http://csunplugged.org/routing-and-deadlock Snail Mail - http://www.cs4fn.org/internet/realsnailmail.php Code.org - The Internet https://learn.code.org/s/1/level/102

15.6.3. Useful Links

http://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/TCP/IP http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_protocol_suite http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypertext_Transfer_Protocol http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_Relay_Chat http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transmission_Control_Protocol http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User_Datagram_Protocol http://csunplugged.org/routing-and-deadlock