EncryptionCoding

8. 暗号符号化

8.1. 概要

暗号化は,データを秘密にしておくのに用いられます.暗号化の簡単な形としては,ファイルやデータ転送中の中身は変換され,秘密の鍵を持つことが許された人だけが原文に戻すことができるというものです.私たちが電子機器を使用している時は,常に暗号化に利用したシステムを使用している可能性があります.例えば,オンラインバンキング,無線LANを利用している時,ブラウザにパスワードを記憶させている時や,クレジットカードで支払いをしている時(カードを読取機に読み取らせている時や,ボタンを押している時)など,実際のほとんどの利用場面で暗号化の機能が使われています.暗号化無しでは,私たちの情報を世界中に見せていることになります.例えば,誰でも無線LANで通信されているデータをすべて読むことができたり,盗まれたノートパソコンやハードディスク,携帯電話などから私たちに関するいろいろな情報を取り出すことができたりします.従って,暗号化はコンピュータシステムを使う上で非常に重要な役割を果たしているのです.

もちろん,誰もが正直で信頼できて,私たちの健康状態の記録,オンラインチャットの内容や,銀行口座などの個人情報に誰がアクセスしても問題なく,そして,飛行機の操縦システムやコンピュータ制御の武器などに誰もアクセスしようとしないことが分かっているような世界に私たちが住んでいるのであれば暗号化は必要ではないでしょう.しかし,情報はお金になる価値があり,人々は自分たちのプライバシーを尊重し,安全は重要です.そのため,暗号化はコンピュータシステムのデザインの基本となった.交通信号のシステム上でのセキュリティが破られることでさえ,個人的な利益に使われる場合もあるのです!

すべてのテクノロジーと同様に,暗号化も善悪の両方の目的で使うことができます.人権団体はメディアに人権侵害の写真を密かに送るために暗号化を使うかもしれません.一方で,麻薬密売人は彼らの計画が麻薬捜査官によって読まれることを避けるために暗号化を使うかもしれません.暗号化がどのように働くのか,何が可能なのかを理解することは,言論の自由,人権,犯罪行為の追跡,個人のプライバシー,ID泥棒,オンラインバンキングやオンライン払込や,侵入されたら支配されてしまうといったシステムの安全に関わる決定を下す手助けとなります.

暗号化システムは,実はたった2つのプログラムで構成されています:一つはデータ(平文と呼ばれる)を無意味な文字列(暗号文)に暗号化するプログラムで,もう一つは暗号文を解読して平文に戻すプログラムです.

もちろん,暗号化技術がすべての我々のセキュリティ問題を解決するというわけではありません.私たちに利用可能なとても良い暗号化システムがあっても,情報泥棒は社会工学的アプローチといった他の方法を使ってくるからです.ユーザーのパスワードを手に入れる最も簡単な方法は,ユーザーに尋ねることなのです!フィッシング攻撃とは正にその様なやり方を行います.そして20人に一人位の割合でユーザーは何らかの場面で,この様な方法で秘密の情報を教えてしまっていると考えられています.他の社会工学的アプローチで使われる方法は,システムにアクセスできる人を買収したり脅迫したりして情報を得たり,コンピュータのモニターに貼られているパスワードが書かれている付箋紙を探すなどして得ることなどです.また,他人の電子メールのアカウントにアクセスできる様になると,特に簡単に多くのパスワードを得ることができます.これは,パスワードを忘れた時に使われる多くのシステムでは,新しいパスワード情報をユーザーの電子メールアドレスに送るようになっているからです.

暗号化の方法に話を戻しましょう.そして,コンピュータを十分に安全にするのに必要とされていることは何か,そして個人情報にアクセスするために社会工学を用いなければならないのかについて見ていきましょう.

8.2 Substitution Ciphers

8.2.1 初めに−換字式暗号(かえじしきあんごう)

In this section, we will be looking at a simple substitution cipher called Caesar Cipher. Caesar Cipher is over 2000 years old, invented by a guy called Julius Caesar. Before we go any further, have a go at cracking this simple code. If you're stuck, try working in a small group with friends and classmates so that you can discuss ideas. A whiteboard or pen and paper would be helpful for doing this exercise.

DRO BOCMEO WSCCSYX GSVV ECO K ROVSMYZDOB, KBBSFSXQ KD XYYX DYWYBBYG. LO BOKNI DY LBOKU YED KC CYYX KC IYE ROKB DRBOO LVKCDC YX K GRSCDVO. S'VV LO GOKBSXQ K BON KBWLKXN.

Once you have figured out what the text says, make a table with the letters of the alphabet in order and then write the letter they are represented with in the cipher text. You should notice an interesting pattern.

Given how easily broken this cipher is, you probably don't want your bank details encrypted with it. In practice, far stronger ciphers are used, although for now we are going to look a little bit further at Caesar Cipher, because it is a great introduction to the many ideas in encryption.

8.2.2 How does the Caesar Cipher work?

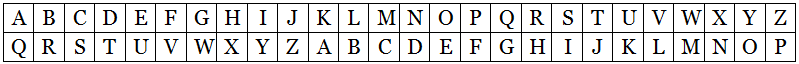

When you looked at the Caesar Cipher in the previous section and (hopefully) broke it and figured out what it said, you probably noticed that there was a pattern in how letters from the original message corresponded to letters in the decoded one. Each letter in the original message decoded to the letter that was 10 places before it in the alphabet. The conversion table you drew should have highlighted this. Here's the table for the letter correspondences, where the letter "K" translates to an "A". It is okay if your conversion table mapped the opposite way, i.e. "A" to "K" rather than "K" to "A". If you were unable to break the Caesar Cipher in the previous section, go back to it now and decode it using the table.

For this example, we say the key is 10 because keys in Caesar Cipher are a number between 1 and 25 (think carefully about why we wouldn't want a key of 26!), which specify how far the alphabet should be rotated. If instead we used a key of 8, the conversion table would be as follows.

Jargon Buster: What is key?

In a Caesar Cipher, the key represents how many places the alphabet should be rotated. In the examples above, we used keys of "8" and "10". More generally though, a key is simply a value that is required to do the math for the encryption and decryption. While Caesar Cipher only has 25 possible keys, real encryption systems have an incomprehensibly large number of possible keys, and preferably use keys which contains hundreds or even thousands of binary digits. Having a huge number of different possible keys is important, because it would take a computer less than a second to try all 25 Caesar Cipher keys.

In the physical world, a combination lock is completely analagous to a cipher (in fact, you could send a secret message in a box locked with a combination lock.) We'll assume that the only way to open the box is to work out the combination number. The combination number is the key for the box. If it's a three-digit lock, you'll only have 1000 values to try out, which might not take too long. A four-digit lock has 10 times as many values to try out, so is way more secure. Of course, there may be ways to reduce the amount of work required - for example, if you know that the person who locked it never has a correct digit showing, then you only have 9 digits to guess for each place, rather than 10, which would take less than three quarters of the time!

Try experimenting with the following interactive for Caesar Cipher. You will probably want to refer back to it later while working through the remainder of the sections on Caesar Cipher.

8.2.2.1 Decryption with Caesar Cipher

Before we looked at how to crack Casear cipher – getting the plaintext from the ciphertext without being told the key beforehand. It is even easier to decrypt Caesar Cipher when we do have the key. In practice, a good encryption system ensures that the plaintext cannot be obtained from the ciphertext without the key, i.e. it can be decrypted but not cracked.

As an example of decrypting with Caesar Cipher, assume that we have the following ciphertext, and that the key is 6.

ZNK WAOIQ HXUCT LUD PASVY UBKX ZNK RGFE JUM.

Because we know that the key is 6, we can subtract 6 places off each character in the ciphertext. For example, the letter 6 places before "Z" is "T", 6 places before "N" is "H", and 6 places before "K" is "E". From this, we know that the first word must be "THE". Going through the entire ciphertext in this way, we can eventually get the plaintext of:

THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG

The interactive above can do this process for you. Just put the ciphertext into the box on the right, enter the key, and tell it to decrypt. You should ensure you understand how to encrypt messages yourself though!

Challenge: Decrypting a Caesar Cipher

Challenge 1

Decrypt the following message using Caesar Cipher. The key is 4.

HIGVCTXMRK GEIWEV GMTLIV MW IEWC

Challenge 2

What is the key for the following cipher text?

THIS IS A TRICK QUESTION

8.2.2.2. Encryption with Caesar Cipher

Encryption is equally straightforward. Instead of rotating backwards (subtracting) like we did for decrypting, we rotate forwards (add) the key to each letter in the plaintext. For example, assume we wanted to encrypt the following text with a key of 7.

HOW ARE YOU

We would start by working that the letter that is 7 places ahead of "H" is "O", 7 places ahead of "O" is "V", and 7 places ahead of "W" is "D". This means that the first word of the plaintext encrypts to "OVD" in the ciphertext. Going through the the entire plaintext in this way, we can eventually get the ciphertext of:

OVD HYL FVB

Challenge: Encrypting with Caesar Cipher

Challenge 1

Encrypt the following message using Caesar Cipher and a key of 20

JUST ANOTHER RANDOM MESSAGE TO ENCRYPT

Challenge 2

Why is using a key of 26 on the following message not a good idea?

USING A KEY OF TWENTY SIX IN CAESAR CIPHER IS NOT A GOOD IDEA

Curiosity: ROT13 Caesar Cipher

The Caesar cipher with a key of 13 is the same as an approach called ROT13 (rotate 13 characters), which is sometimes used to obscure things like the punchline of a joke, a spoiler for a story, the answer to a question, or text that might be offensive. It is easy to decode (and there are plenty of automatic systems for doing so), but the user has to deliberately ask to see the deciphered version. A key of 13 for a Caesar cipher has the interesting property that the encryption method is identical to the decryption method i.e. the same program can be used for both. Many strong encryption methods try to make the encryption and decryption processes as similar as possible so that the same software and/or hardware can be used for both parts of the task, generally with only minor adaptions.

8.2.3. Problems with Substitution Ciphers

Jargon Buster: What is a substitution cipher?

A substitution cipher simply means that each letter in the plaintext is substituted with another letter to form the ciphertext. If the same letter occurs more than once in the plaintext then it appears the same at each occurrence in the ciphertext. For example the phrase "HELLO THERE" has multiple H's, E's, and L's. All the H's in the plaintext might change to "C" in the ciphertext for example. Casear Cipher is an example of a substitution cipher. Other substitution ciphers improve on the Caesar cipher by not having all the letters in order, and some older written ciphers use different symbols for each symbol. However, substitution ciphers are easy to attack because a statistical attack is so easy: you just look for a few common letters and sequences of letters, and match that to common patterns in the language.

So far, we have considered one way of cracking Caesar cipher: using patterns in the text. By looking for patterns such as one letter words, other short words, double letter patterns, apostrophe positions, and knowing rules such as all words must contain at least one of a, e, i, o, u, or y (excluding some acronyms and words written in txt language of course), cracking Caesar Cipher by looking for patterns is easy. Any good cryptosystem should not be able to be analysed in this way, i.e. it should be semantically secure

Jargon Buster: What do we mean by semantically secure?

Semantically secure means that there is no known efficient algorithm that can use the ciphertext to get any information about the plaintext, other than the length of the message. It is very important that cryptosystems used in practice are semantically secure.

As we saw above, Caesar Cipher is not semantically secure.

There are many other ways of cracking Caeser cipher which we will look at in this section. Understanding various common attacks on ciphers is important when looking at sophisticated cryptosystems which are used in practice.

8.2.3.1. Frequency Analysis Attacks

Frequency analysis means looking at how many times each letter appears in the encrypted message, and using this information to crack the code. A letter that appears many times in a message is far more likely to be “T” than “Z”, for example.

The following interactive will helps you to analyze a piece of text by counting up the letter frequencies. You can paste in some text to see which are the most common (and least common) characters.

The following text has been coded using a Caesar cipher. To try to make sense of it, paste it into the statistical analyser above.

F QTSL RJXXFLJ HTSYFNSX QTYX TK XYFYNXYNHFQ HQZJX YMFY HFS GJ ZXJI YT FSFQDXJ BMFY YMJ RTXY KWJVZJSY QJYYJWX FWJ, FSI JAJS YMJ RTXY HTRRTS UFNWX TW YWNUQJX TK QJYYJWX HFS MJQU YT GWJFP YMJ HTIJ

"E" is the most common letter in the English alphabet. It is therefore a reasonable guess that "J" in the ciphertext represents "E" in the plaintext. Because "J" is 5 letters ahead of "E" in the alphabet, we can guess that the key is 5. If you put the ciphertext into the above interactive and set a key of 5, you will find that this is indeed the correct key.

★コンテンツは準備中です★

Spoiler: Decrypted message

The message you should have decrypted is:

A LONG MESSAGE CONTAINS LOTS OF STATISTICAL CLUES THAT CAN BE USED TO ANALYSE WHAT THE MOST FREQUENT LETTERS ARE, AND EVEN THE MOST COMMON PAIRS OR TRIPLES OF LETTERS CAN HELP TO BREAK THE CODE

As the message says, long messages contain a lot of statistical clues. Very short messages (e.g. only a few words) are unlikely to have obvious statistical trends. Very long messages (e.g. entire books) will almost always have "E" as the most common letter. Wikipedia has a list of letter frequencies, which you might find useful.

Challenge: Frequency Analysis

Put the ciphertext into the above frequency analyser, guess what the key is (using the method explained above), and then try using that key with the ciphertext in the interactive above. Try to guess the key with as few guesses as you can!

Challenge 1

WTGT XH PCDIWTG BTHHPVT IWPI NDJ HWDJAS WPKT CD IGDJQAT QGTPZXCV LXIW ATIITG UGTFJTCRN PCPANHXH

Challenge 2

OCDN ODHZ OCZ HZNNVBZ XJIOVDIN GJON JA OCZ GZOOZM O, RCDXC DN OCZ NZXJIY HJNO XJHHJI GZOOZM DI OCZ VGKCVWZO

Challenge 3

BGDTCU BCEJ, BCXKGT, CPF BCPG BQQOGF VJTQWIJ VJG BQQ

Curiosity: The letter E isn't always the most common letter...

Although in almost all English texts the letter E is the most common letter, it isn't always. For example, the 1939 novel Gadsby by Ernest Vincent Wright doesn't contain a single letter E (this is called a lipogram). Furthermore, the text you're attacking may not be English. During World War 1 and 2, the US military had many Native American Code talkers translate messages into their own language, which provided a strong layer of security at the time.

Curiosity: The Vigenere Cipher

A slightly stronger cipher than the Caesar cipher is the Vigenere cipher, which is created by using multiple Caesar ciphers, where there is a key phrase (e.g. "acb"), and each letter in the key gives the offset (in the example this would be 1, 3, 2). These offsets are repeated to give the offset for encoding each character in the plaintext.

By having multiple Caesar ciphers, common letters such as E will no longer stand out as much, making frequency analysis a lot more challenging. The following website shows the effect on the distribution. http://www.simonsingh.net/The_Black_Chamber/vigenere_strength.html

However, while this makes the Vigenere cipher more challenging to crack than the Caeser cipher, ways have been found to crack it quickly. In fact, once you know the key length, it just breaks down to cracking several Caesar ciphers (which as you have seen is straightforward, and you can even use frequency analysis on the individual Caesar Ciphers!) Several statistical methods have been devised for working out the key length.

Attacking the Vigenere cipher by trying every possible key is hard because there are a lot more possible keys than for the Caesar cipher, but a statistical attack can work quite quickly. The Vigenere cipher is known as a polyalphabetic substitution cipher, since it is uses multiple substitution rules.

8.2.3.2. Known Plain Text Attacks

Another kind of attack is the known plaintext attack, where you know part or all of the solution. For example, if you know that I start all my messages with "HI THERE", you can easily determine the key for the following message.

AB MAXKX LXVKXM FXXMBGZ TM MPH TF MANKLWTR

Even if you did not know the key used a simple rotation (not all substitution ciphers are), you have learnt that A->H, B->I, M->T, X->E, and K->R. This goes a long way towards deciphering the message. Filling in the letters you know, you would get:

AB MAXKX LXVKXM FXXMBGZ TM MPH TF MANKLWTR HI THERE _E__ET _EETI__ _T T__ __ TH______

By using the other tricks above, there are a very limited number of possibilities for the remaining letters. Have a go at figuring it out.

Spoiler: The above message is...

The deciphered message is:

HI THERE SECRET MEETING AT TWO AM THURSDAY

A known plaintext attack breaks a Caesar cipher straight away, but a good cryptosystem shouldn't have this vulnerability because it can be surprisingly easy for someone to know that a particular message is being sent. For example, a common message might be "Nothing to report", or in online banking there are likely to be common messages like headings in a bank account or parts of the web page that always appear. Even worse is a chosen plaintext attack, where you trick someone into sending your chosen message through their system so that you can see what its ciphertext is.

For this reason, it is essential for any good cryptosystem to not be breakable, even if the attacker has pieces of plaintext along with their corresponding ciphertext to work with. For this, the cryptosystem should give different ciphertext each time the same plaintext message is encrypted. It may initially sound impossible to achieve this, although there are several clever techniques used by real cryptosystems.

Curiosity: More general substitution ciphers

While Caesar cipher has a key specifying a rotation, a more general substitution cipher could randomly scramble the entire alphabet. This requires a key consisting of a sequence of 26 letters or numbers, specifying which letter maps onto each other one. For example, the first part of the key could be “D, Z, E”, which would mean D: A, Z: B, E:C. The key would have to have another 23 letters in order to specify the rest of the mapping.

This increases the number of possible keys, and thus reduces the risk of a brute force attack. A can be substituted for any of the 26 letters in the alphabet, B can then be substituted for any of the 25 remaining letters (26 minus the letter already substituted for A), C can then be substituted for any of the 24 remaining letters…

This gives us 26 possibilities for A times 25 possibilities for B times 24 possibilities for C.. all the way down to 2 possibilities for Y and 1 possibility for Z. 26×25×24×23×22×21×20×19×18×17×16×15×14×13×12×11×10×9×8×7×6×5×4×3×2×1=26!26×25×24×23×22×21×20×19×18×17×16×15×14×13×12×11×10×9×8×7×6×5×4×3×2×1=26! Representing each of these possibilities requires around 88 bits, making the cipher’s key size around 88 bits, which is below modern standards, although still not too bad!

However, this only solves one of the problems. The other techniques for breaking Caeser cipher we have looked at are still highly effective on all substitution ciphers, in particular the frequency analysis. For this reason, we need better ciphers in practice, which we will look at shortly.

8.2.3.3. Brute force Attacks

Another approach to cracking a ciphertext is a brute force attack, which involves trying out all possible keys, and seeing if any of them produce intelligible text. This is easy for a Caesar cipher because there are only 25 possible keys. For example, the following ciphertext is a single word, but is too short for a statistical attack. Try putting it into the decoder above, and trying keys until you decipher it.

EIJUDJQJYEKI

These days encryption keys are normally numbers that are 128 bits or longer. You could calculate how long it would take to try out every possible 128 bit number if a computer could test a million every second (including testing if each decoded text contains English words). It will eventually crack the message, but after the amount of time it would take, it's unlikely to be useful anymore – and the user of the key has probably changed it!

In fact, if we analyse it, a 128 bit key at 1,000,000 per second would take 10,790,283,070,000,000,000,000,000 years to test. Of course, it might find something in the first year, but the chances of that are ridiculously low, and it would be more realistic to hope to win the top prize in Lotto three times consecutively (and you'd probably get more money). On average, it will take around half that amount, i.e. a bit more than 5,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years. Even if you get a really fast computer that can check one trillion keys a second (rather unrealistic in practice), it would still take around 5,000,000,000,000 years. Even if you could get one million of those computers (even more unrealistic in practice), it would still take 5,000,000 years.

And even if you did have the hardware that was considered above, then people would start using bigger keys. Every bit added to the key will double the number of years required to guess it. Just adding an extra 15 or 20 bits to the key in the above example will safely push the time required back to well beyond the expected life span of the Earth and Sun! This is how real cryptosystems protect themselves from brute force attacks. Cryptography relies a lot on low probabilities of success.

The calculator below can handle really big numbers. You can double check our calculations above if you want! Also, work out what would happen if the key size was double (i.e. 256 bits), or if a 1024 or 2048 bit key (common these days) was used.

Curiosity: Tractability – problems that take too long to solve

Brute force attacks try out every possible key, and the number of possible keys grows exponentially as the key gets longer. As we saw above, no modern computer system could try out all possible 128 bit key values in a useful amount of time, and even if it were possible, adding just one more bit would double how long it would take.

In computer science, problems that take an exponential amount of time to solve are generally regarded as not being tractable --- that is, you can't get any traction on them; it's as if you're spinning your wheels. Working out which problems are tractable and which are intractable is a major area of research in computer science --- many other problems that we care about appear to be intractable, much to our frustration. The area of encryption is one of the few situations where we're pleased that an algorithm is intractible!

This guide has a whole chapter about tractability chapter, where you can explore these issues further.

Jargon Buster: Terminology you should now be familiar with

The main terminology you should be familiar with now is that a plaintext is encrypted by to create a ciphertext using an encryption key. Someone without the encryption key who wants to attack the cipher could try various approaches, including a brute force attack (trying out all possible keys), a frequency analysis attack (looking for statistical patterns), and a known plaintext attack (matching some known text with the cipher to work out the key).

If you were given an example of a simple cipher being used, you should be able to talk about it using the proper terminology.

しかしこの暗号化の方法はあまり安全ではありません.もしかしたら,皆さんは既にどうやったらこの暗号を破れば良いかを見抜いているかもしれませんね.実は,対応している文字セットが1文字分かるだけでよいのです.それが分かれば,どのくらい回転すれば良いか計算でき,それが鍵(キー)になるのです.

8.3. Cryptosystems used in practice

The substitution systems described above don't provide any security for modern digital systems. In the remainder of this chapter we will look at encryption systems that are used in practice. The first challenge is to find a way to exchange keys --- after all, if you're communicating to someone over the internet, how are you going to send the key for your secret message to them conveniently?

Cryptosystems are also used for purposes such as authentication (checking a password). This sounds simple, but how do you check when someone logs in, without having to store their password (after all, if someone got hold of the password list, that could ruin your reputation and business, so it's even safer not to store them.)

There are good solutions to these problems that are regularly used --- in fact, you probably use them online already, possibly without even knowing! We'll begin by looking at systems that allow people so decode secret messages without even having to be sent the key!

8.4. The Key Distribution Problem

Curiosity: Who are Alice, Bob, and Eve?

When describing an encryption scenario, cryptographers often use the fictitious characters "Alice" and "Bob", with a message being sent from Alice to Bob (A to B). We always assume that someone is eavesdropping on the conversation (in fact, if you're using a wireless connection, it's trivial to pick up the transmissions between Alice and Bob as long as you're in reach of the wireless network that one of them is using). The fictitious name for the eavesdropper is usually Eve.

There are several other characters used to describe activities around encryption protocols: for example Mallory (a malicious attacker) and Trudy (an intruder). Wikipedia has a list of Alice and Bob's friends

If Alice is sending an encrypted message to Bob, this raises an interesting problem in encryption. The ciphertext itself can safely be sent across an “unsafe” network (one that Eve is listening on), but the key cannot. How can Alice get the key to Bob? Remember the key is the thing that tells Bob how to convert the ciphertext back to plaintext. So Alice can’t include it in the encrypted message, because then Bob would be unable to access it. Alice can’t just include it as plaintext either, because then Eve will be able to get ahold of it and use it to decrypt any messages that come through using it. You might ask why Alice doesn’t just encrypt the key using a different encryption scheme, but then how will Bob know the new key? Alice would need to tell Bob the key that was used to encrypt it... and so on... this idea is definitely out!

Remember that Alice and Bob might be in different countries, and can only communicate through the internet. This also rules out Alice simply passing Bob the key in person.

Curiosity: Are we being paranoid?

In computer security we tend to assume that Eve, the eaves dropper, can read every message between Alice and Bob. This sounds like an inordinate level of wire tapping, but what about wireless systems? If you're using wireless (or a mobile phone), then all your data is being broadcast, and can be picked up by any wireless receiver in the vicinity. In fact, if another person in the room is also using wireless, their computer is already picking up everything being transmitted by your computer, and has to go to some trouble to ignore it.

Even in a wired connection, data is passed from one network node to another, stored on computers inbetween. Chances are that everyone who operates those computers is trustworthy, but probably don't even know which companies have handled your data in the last 24 hours, let alone whether every one of their employees can be trusted.

So assuming that somone can observe all the bits being transmitted and received from your computer is pretty reasonable.

Distributing keys physically is very expensive, and up to the 1970s large sums of money were spent physically sending keys internationally. Systems like this are call symmetric encryption, because Alice and Bob both need an identical copy of the key. The breakthrough was the realisation that you could make a system that used different keys for encoding and decoding. We will look further at this in the next section.

Curiosity: Some additional viewing

Simon Singh's video gives a good explanation of key distribution.

Additionally, there's a video illustrating how public key systems work using a padlock analogy.

8.4.1. Public Key Systems

One of the remarkable discoveries in computer science in the 1970s was a method called public key encryption, where it's fine to tell everyone what the key is to encrypt any messages, but you need a special private key to decrypt it. Because Alice and Bob use different keys, this is called an asymmetric encryption system.

It's like giving out padlocks to all your friends, so anyone can lock a box and send it to you, but if you have the only (private) key, then you are the only person who can open the boxes. Once your friend locks a box, even they can't unlock it. It's really easy to distribute the padlocks. Public keys are the same – you can make them completely public – often people put them on their website or attach them to all emails they send. That's quite different to having to hire a security firm to deliver them to your colleagues.

Public key encryption is very heavily used for online commerce (such as internet banking and credit card payment) because your computer can set up a connection with the business or bank automatically using a public key system without you having to get together in advance to set up a key. Public key systems are generally slower than symmetric systems, so the public key system is often used to then send a new key for a symmetric system just once per session, and the symmetric key can be used from then on with a faster symmetric encryption system.

A very popular public key system is RSA. For this section on public key systems, we will use RSA as an example.

8.4.1.1. Generating the encryption and decryption keys

Firstly, you will need to generate a pair of keys using the key generator interactive. You should keep the private key secret, and publicly announce the public key so that your friends can send you messages (e.g. put it on the whiteboard, or email it to some friends). Make sure you save your keys somewhere so you don’t forget them – a text file would be best.

8.4.1.2. Encrypting messages with the public key

This next interactive is the encrypter, and it is used to encrypt messages with your public key. Your friends should use this to encrypt messages for you.

To ensure you understand, try encrypting a short message with your public key. In the next section, there is an interactive that you can then use to decrypt the message with your private key.

8.4.1.3. Decrypting messages with the private key

Finally, this interactive is the decrypter. It is used to decrypt messages that were encrypted with your public key. In order to decrypt the messages, you will need your private key.

Despite even your enemies knowing your public key (as you publicly announced it), they cannot use it to decrypt your messages which were encrypted using the public key. You are the only one who can decrypt messages, as that requires the private key which hopefully you are the only one who access to.

Note that this interactive’s implementation of RSA only uses around 50 bits of encryption and has other weaknesses. It is just for demonstrating the concepts here and is not quite the same as the implementations used in live encryption systems.

Curiosity: Can we reverse the RSA calculations?

If you were asked to multiply the following two big prime numbers, you might find it a bit tiring to do by hand (although it is definitely achievable), and you could get an answer in a fraction of a second using a computer.

97394932817749829874327374574392098938789384897239489848732984239898983986969870902045828438234520989483483889389687489677903899

34983724732345498523673948934032028984850938689489896586772739002430884920489508348988329829389860884285043580020020020348508591

If on the other hand you were asked which two prime numbers were multiplied to get the following big number, you’d have a lot more trouble! (If you do find the answer, let us know! We’d be very interested to hear about it!)

3944604857329435839271430640488525351249090163937027434471421629606310815805347209533599007494460218504338388671352356418243687636083829002413783556850951365164889819793107893590524915235738706932817035504589460835204107542076784924507795112716034134062407

Creating an RSA code involves doing the multiplication above, which is easy for computers. If we could solve the second problem and find the multiples for a big number, we'd be able to crack an RSA code. However, no one knows a fast way to do that. This is called a "trapdoor" function - it's easy to go into the trapdoor (multiply two numbers), but it's pretty much impossible to get back out (find the two factors).

So why is it that despite these two problems being similar, one of them is “easy” and the other one is “hard”? Well, it comes down to the algorithms we have to solve each of the problems.

You have probably done long multiplication in school by making one line for each digit in the second number and then adding all the rows together. We can analyse the speed of this algorithm, much like we did in the algorithms chapter for sorting and searching. Assuming that each of the two numbers has the same number of digits, which we will call n (“Number of digits”), we need to write n rows. For each of those n rows, we will need to do around n multiplications. That gives us n×nn×n little multiplications. We need to add the n rows together at the end as well, but that doesn’t take long so lets ignore that part. We have determined that the number of small multiplications needed to multiply two big numbers is approximately the square of the number of digits. So for two numbers with 1000 digits, that’s 1,000,000 little multiplication operations. A computer can do that in less than a second! If you know about Big-O notation, this is an O(n2)O(n2) algorithm, where n is the number of digits. Note that some slightly better algorithms have been designed, but this estimate is good enough for our purposes.

For the second problem, we’d need an algorithm that could find the two numbers that were multiplied together. You might initially say, why can’t we just reverse the multiplication? The reverse of multiplication is division, so can’t we just divide to get the two numbers? It’s a good idea, but it won’t work. For division we need to know the big number, and one of the small numbers we want to divide into it, and that will give us the other small number. But in this case, we only know the big number. So it isn’t a straightforward long division problem at all! It turns out that there is no known fast algorithm to solve the problem. One way is to just try dividing by every number that is less than the number (well, we only need to go up to the square root, but that doesn’t help much!) There are still billions of billions of billions of numbers we need to check. Even a computer that could check 1 billion possibilities a second isn’t going to help us much with this! If you know about Big-O notation, this is an O(10n)O(10n) algorithm, where n is the number of digits -- even small numbers of digits are just too much to deal with! There are slightly better solutions, but none of them shave off enough time to actually be useful for problems of the size of the one above!

The chapter on complexity and tractability looks at more computer science problems that are surprisingly challenging to solve. If you found this stuff interesting, do read about Complexity and Tractability when you are finished here!

Curiosity: Encrypting with the private key instead of the public key --- Digital Signatures!

In order to encrypt a message, the public key is used. In order to decrypt it, the corresponding private key must be used. But what would happen if the message was encrypted using the private key? Could you then decrypt it with the public key?

Initially this might sound like a pointless thing to do --- why would you encrypt a message that can be decrypted using a key that everybody in the world can access!?! It turns out that indeed, encrypting a message with the private key and then decrypting it with the public key works, and it has a very useful application.

The only person who is able to encrypt the message using the private key is the person who owns the private key. The public key will only decrypt the message if the private key that was used to encrypt it actually is the public key’s corresponding private key. If the message can’t be decrypted, then it could not have been encrypted with that private key. This allows the sender to prove that the message actually is from them, and is known as a .

You could check that someone is the authentic private key holder by giving them a phrase to encrypt with their private key. You then decrypt it with the public key to check that they were able to encrypt the phrase you gave them.

This has the same function as a physical signature, but is more reliable because it is essentially impossible to forge. Some email systems use this so that you can be sure an email came from the person who claims to be sending it.

8.5. Storing Passwords Securely

A really interesting puzzle in encryption is storing passwords in a way that even if the database with the passwords gets leaked, the passwords are not in a usable form. Such a system has many seemingly conflicting requirements.

- When a user logs in, it must be possible to check that they have entered the correct password.

- Even if the database is leaked, and the attacker has huge amounts of computing power...

- The database should not give away obvious information, such as password lengths, users who chose the same passwords, letter frequencies of the passwords, or patterns in the passwords.

- At the very least, users should have several days/ weeks to be able to change their password before the attacker cracks it. Ideally, it should not be possible for them to ever recover the passwords.

- There should be no way of recovering a forgotten password. If the user forgets their password, it must be reset. Even system administrators should not have access to a user's password.

Most login systems have a limit to how many times you can guess a password. This protects all but the poorest passwords from being guessed through a well designed login form. Suspicious login detection by checking IP address and country of origin is also becoming more common. However, none of these application enforced protections are of any use once the attacker has a copy of the database and can throw as much computational power at it as they want, without the restrictions the application enforces. This is often referred to "offline" attacking, because the attacker can attack the database in their own time.

In this section, we will look at a few widely used algorithms for secure password storage. We will then look at a couple of case studies where large databases were leaked. Secure password storage comes down to using clever encryption algorithms and techniques, and ensuring users choose effective passwords. Learning about password storage might also help you to understand the importance of choosing good passwords and not using the same password across multiple important sites.

8.5.1. Hashing passwords

A hashing algorithm is an algorithm that takes a password and performs complex computations on it and then outputs a seemingly random string of characters called a hash. This process is called hashing. Good hashing algorithms have the following properties:

- Each time a specific password is hashed, it should give the same hash.

- Given a specific hash, it should be impossible to efficiently compute what the original password was.

Mathematically, a hashing algorithm is called a "one way function". This just means that it is very easy to compute a hash for a given password, but trying to recover the password from a given hash can only be done by brute force. In other words, it is easy to go one way, but it is almost impossible to reverse it. A popular algorithm for hashing is called SHA-256. The remainder of this chapter will focus on SHA-256.

Jargon Buster: What is meant by brute force?

In the Caesar Cipher section, we talked briefly about brute force attacks. Brute force attack in that context meant trying every possible key until the correct one was found.

More generally, brute force is trying every possibility until a solution is found. For hashing, this means going through a long list of possible passwords, running each through the hashing algorithm, and then checking if the outputted hash is identical to the one that we are trying to reverse.

For passwords, this is great. Instead of storing passwords in our database, we can store hashes. When a user signs up or changes their password, we simply need to put the password through the SHA-256 algorithm and then store the output hash instead of the password. When the user wants to log in, we just have to put their password through the SHA-256 algorithm again. If the output hash matches the one in the database, then the user has to have entered the correct password. If an attacker manages to access the password database, they cannot determine what the actual passwords are. The hashes themselves are not useful to the attacker.

The following interactive allows you to hash words, such as passwords (but please don't put your real password into it, as you should never enter your password on random sites). If you were to enter a well chosen password (e.g. a random string of numbers and letters), and it was of sufficient length, you could safely put the hash on a public website, and nobody would be able to determine what your actual password was.

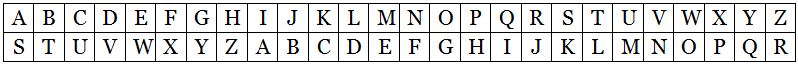

For example, the following database table shows four users of a fictional system, and the hashes of their passwords. You could determine their passwords by putting various possibilities through SHA-256 and checking whether or not the output is equivalent to any of the passwords in the database.

It might initially sound like we have the perfect system. But unfortunately, there is still a big problem. You can find rainbow tables online, which are precomputated lists of common passwords with what value they hash to. It isn't too difficult to generate rainbow tables containing all passwords up to a certain size in fact (this is one reason why using long passwords is strongly recommended!) This problem can be avoided by choosing a password that isn't a common word or combination of words.

Hashing is a good start, but we need to further improve our system so that if two users choose the same password, their hash is not the same, while still ensuring that it is possible to check whether or not a user has entered the correct password. The next idea, salting, addresses this issue.

Curiosity: Passwords that hash to the same value

When we said that if the hashed password matches the one in the database, then the user has to have entered the correct password, we were not telling the full truth. Mathematically, we know that there has to be passwords which would hash to the same value. This is because the length of the output hash has a maximum length, whereas the password length (or other data being hashed) could be much larger. Therefore, there are more possible inputs than outputs, so some inputs must have the same output. When two different inputs have the same output hash, we call it a collision.

Currently, nobody knows of two unique passwords which hash to the same value with SHA-256. There is no known mathematical way of finding collisons, other than hashing many values and then trying to find a pair which has the same hash. The probability of finding one in this way is believed to be in the order of 1 in a trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion. With current computing power, nobody can come even close to this without it taking longer than the life of the sun and possibly the universe.

Some old algorithms, such as MD5 and SHA-1 were discovered to not be as immune to finding collisions as was initially thought. It is possible that there are ways of finding collisions more efficiently than by luck. Therefore, their use is now discouraged for applications where collisions could cause problems.

For password storage, collisions aren't really an issue anyway. Chances are, the password the user selected is somewhat predictable (e.g. a word out of a dictionary, with slight modifications), and an attacker is far more likely to guess the original password than one that happens to hash to the same value as it.

But hashing is used for more than just password storage. It is also used for digital signatures, which must be unique. For those applications, it is important to ensure collisions cannot be found.

8.5.2. Hashing passwords with a salt

A really clever technique which solves some of the problems of using a plain hash is salting. Salting simply means to attach some extra data, called salt, onto the end of the password and then hash the combined password and salt. Normally the salt is quite large (e.g. 128 bits). When a user tries to log in, we will need to know the salt for their password so that it can be added to the password before hashing and checking. While this initially sounds challenging, the salt should not be treated as a secret. Knowing the salt does not help the attacker to mathematically reverse the hash and recover the password. Therefore, a common practice is to store it in plaintext in the database.

So now when a user registers, a long random salt value is generated, added to the end of their password, and the combined password and salt is hashed. The plaintext salt is stored next to the

8.5.3. The importance of good user passwords

If the passwords are salted and hashed, then a rainbow table is useless to the attacker. With current computing power and storage, it is impossible to generate rainbow tables for all common passwords with all possible salts. This slows the attacker down greatly, however they can still try and guess each password one by one. They simply need to guess passwords, add the salt to them, and then check if the hash is the one in the database.

A common brute force attack is a dictionary attack. This is where the attacker writes a simple program that goes through a long list of dictionary words, other common passwords, and all combinations of characters under a certain length. For each entry in the list, the program adds the salt to the entry and then hashes to see if it matches the hash they are trying to determine the password for. Good hardware can check millions, or even billions, of entries a second. Many user passwords can be recovered in less than a second using a dictionary attack.

Unfortunately for end users, many companies keep database leaks very quiet as it is a huge embarrassment that could cripple the company. Sometimes the company doesn't know its database was leaked, or has suspicions that it was but for PR reasons they choose to deny it. In the best case, they might require you to pick a new password, giving a vague excuse. For this reason, it is important to use different passwords on every site to ensure that the attacker does not break into accounts you own on other sites. There is quite possibly passwords or yours that you think nobody knows, but somewhere in the world an attacker has recovered it from a database they broke into.

While in theory, encrypting the salts sounds like a good way to add further security, it isn't as great in practice. We couldn't use a one way hash function (as we need the salt to check the password), so instead would have to use one of the encryption methods we looked at earlier which use a secret key to unlock. This secret key would have to be accessible by the program that checks password (else it can't get the salts it needs to check passwords!), and we have to assume the attacker could get ahold of that as well. The best security against offline brute force attacks is good user passwords.

This is why websites have a minimum password length, and often require a mix of lowercase, uppercase, symbols, and numbers. There are 96 standard characters you can use in a password. 26 upper case letters, 26 lower case letters, 10 digits, and 34 symbols. If the password you choose is completely random (e.g. no words or patterns), then each character you add makes your password 96 times more difficult to guess. Between 8 and 16 characters long can provide a very high level of security, as long as the password is truly random. Ideally, this is the kind of passwords you should be using (and ensure you are using a different password for each site!).

Unfortunately though, these requirements don't work well for getting users to pick good passwords. Attackers know the tricks users use to make passwords that meet the restrictions, but can be remembered. For example, P@$$w0rd contains 8 characters (a commonly used minimum), and contains a mix of different types of characters. But attackers know that users like to replace S's with $'s, mix o and 0, replace i with !, etc. In fact, they can just add these tricks into their list they use for dictionary attacks! For websites that require passwords to have at least on digit, the result is even worse. Many users pick a standard english word and then add a single digit to the end of it. This again is easy work for a dictionary attack to crack!

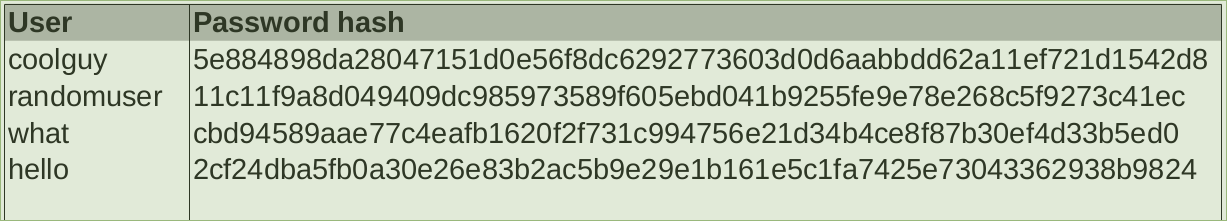

As this xkcd comic points out, most password advice doesn't make a lot of sense.

You might not know what some of the words mean. In easy terms, what it is saying is that there are significantly fewer modifications of common dictionary words than there is of a random selection of four of the 2000 most common dictionary words. Note that the estimates are based on trying to guess through a login system. With a leaked database, the attacker can test billions of passwords a second rather than just a few thousand.

8.5.4. The whole story!

The early examples in this chapter use very weak encryption methods that were chosen to illustrate concepts, but would never be used for commercial or military systems.

There are many aspects to computer security beyond encryption. For example, access control (such as password systems and security on smart cards) is crucial to keeping a system secure. Another major problem is writing secure software that doesn't leave ways for a user to get access to information that they shouldn't (such as typing a database command into a website query and have the system accidentally run it, or overflowing the buffer with a long input, which could accidentally replace parts of the program). Also, systems need to be protected from "denial of service" (DOS) attacks, where they get so overloaded with requests (e.g. to view a web site) that the server can't cope, and legitimate users get very slow response from the system, or it might even fail completely.

For other kinds of attacks relating to computer security, see the Wikipedia entry on Hackers).

There's a dark cloud hanging over the security of all current encryption methods: Quantum computing. Quantum computing is in its infancy, but if this approach to computing is successful, it has the potential to run very fast algorithms for attacking our most secure encryption systems (for example, it could be used to factorise numbers very quickly). In fact, the quantum algorithms have already been invented, but we don't know if quantum computers can be built to run them. Such computers aren't likely to appear overnight, and if they do become possible, they will also open the possibility for new encryption algorithms. This is yet another mystery in computer science where we don't know what the future holds, and where there could be major changes in the future. But we'll need very capable computer scientists around at the time to deal with these sorts of changes!

On the positive side, quantum information transfer protocols exist and are used in practice (using specialised equipment to generate quantum bits); these provide what is in theory a perfect encryption system, and don't depend on an attacker being unable to solve a particular computational problem. Because of the need for specialised equipment, they are only used in high security environments such as banking.

Of course, encryption doesn't fix all our security problems, and because we have such good encryption systems available, information thieves must turn to other approaches, especially social engineering. The easiest way to get a user's password is to ask them! A phishing attack does just that, and there are estimates that as many as 1 in 20 computer users have given out secret information this way at some stage.

Other social engineering approaches that can be used include bribing or blackmailing people who have access to a system, or simply looking for a password written on a sticky note on someone's monitor! Gaining access to someone's email account is a particularly easy way to get lots of passwords, because many "lost password" systems will send a new password to their email account.

Curiosity: Steganography

Cryptography is about hiding the content of a message, but sometimes it's important to hide the existence of the message. Otherwise an enemy might figure out that something is being planned just because a lot more messages are being sent, even though they can't read them. One way to achieve this is via steganography, where a secret message is hidden inside another message that seems innocuous. A classic scenario would be to publish a message in the public notices of a newspaper or send a letter from prison where the number of letters in each word represent a code. To a casual reader, the message might seem unimportant (and even say the opposite of the hidden one), but someone who knows the code could work it out. Messages can be hidden in digital images by making unnoticable changes to pixels so that they store some information. You can find out more about steganography on Wikipedia or in this lecture on steganography.

Two fun uses of steganography that you can try to decode yourself are a film about ciphers that contains hidden ciphers (called "The Thomas Beale Cipher"), and an activity that has five-bit text codes hidden in music.

8.6. Further reading

The Wikipedia entry on cryptography has a fairly approachable entry going over the main terminology used in this chapter (and a lot more)

The encryption methods used these days rely on fairly advanced maths; for this reason books about encryption tend to either be beyond high school level, or else are about codes that aren’t actually used in practice.

There are lots of intriguing stories around encryption, including its use in wartime and for spying e.g.

- How I Discovered World War II’s Greatest Spy and Other Stories of Intelligence and Code (David Kahn)

- Decrypted Secrets: Methods and Maxims of Cryptology (Friedrich L. Bauer)

- Secret History: The Story of Cryptology (Craig Bauer)

- The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet (David Kahn) - this book is an older version of his new book, and may be hard to get

The following activities explore cryptographic protocols using an Unplugged approach; these methods aren’t strong enough to use in practice, but provide some insight into what is possible:

- http://csunplugged.org/information-hiding

- http://csunplugged.org/cryptographic-protocols

- http://csunplugged.org/public-key-encryption

War in the fifth domain looks at how encryption and security are key to our defence against a new kind of war.

There are lots of articles in cs4fn on cryptography, including a statistical attack that lead to a beheading.

The book “Hacking Secret Ciphers with Python: A beginner’s guide to cryptography and computer programming with Python” (by Al Sweigart) goes over some simple ciphers including ones mentioned in this chapter, and how they can be programmed (and attacked) using Python programs.

8.6.1. Useful Links

- How Stuff Works entry on Encryption <http://www.howstuffworks.com/encryption.htm>

- Cryptool is a free system for trying out classical and modern encryption methods. Some are beyond the scope of this chapter, but many will be useful for running demonstrations and experiments in cryptography.

- Wikipedia entry on Cryptographic keys <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Key_%28cryptography%29>

- Wikipedia entry on the Caesar cipher

- Videos about modern encryption methods

- Online interactives for simple ciphers

Computer Science Field Guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Produced by Tim Bell, Jack Morgan, and many others based at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand.